“All of us experience, or will experience, illness and disability throughout our lives.” So states the wall text in “For Dear Life: Art, Medicine, and Disability,” on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego through February 2.

Accordingly, the show takes a broad view of disability arts. It features artists who openly identify as disabled and make work aligned with the movement for disability justice, as well as those for whom illness and impairment go unnamed.

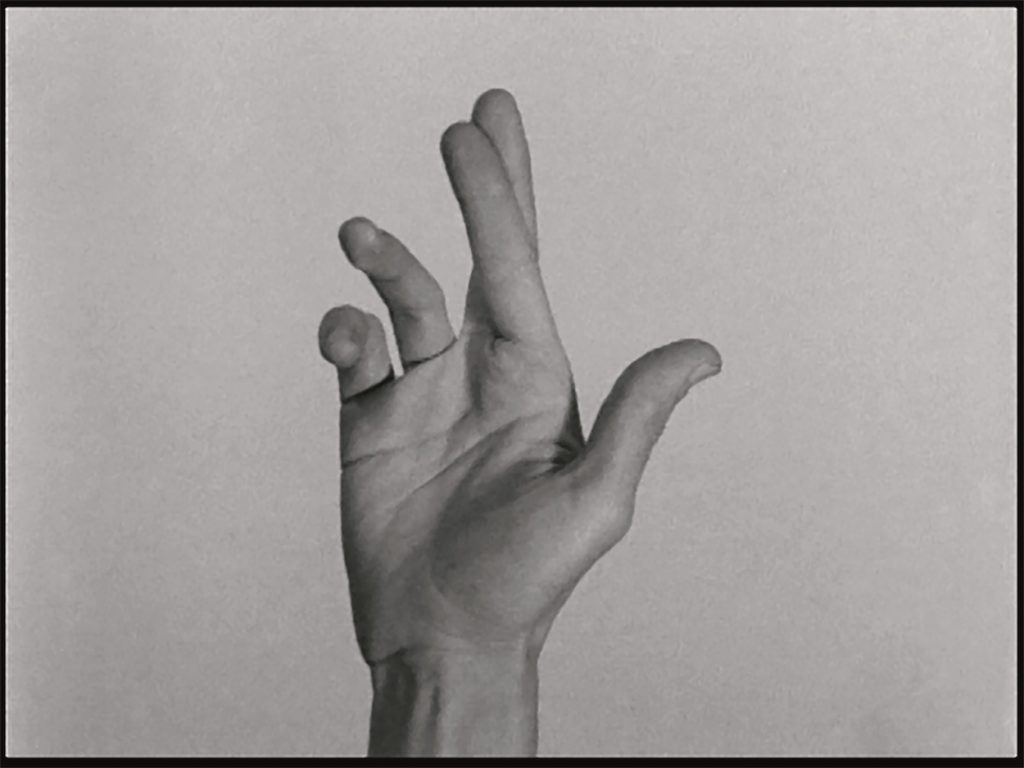

The show begins in the 1960s, with works of feminist art concerned with the body. The opener is Yvonne Rainer’s Hand Movie (1966): a 7-minute work comprising choreography for one hand that she filmed from a hospital bed, while convalescing. The introduction argues that feminism opened space for artists to confront corporeal experiences and oppression based in bodily difference, space to show us not generalized or idealized figures, but messy and personal ones instead.

Works in this section—the show’s strongest—favor fragile materiality. There are canvases covered in hole-punched dots by Howardena Pindell, who began incorporating personal photographs and postcards into her work while recovering from a 1979 car-crash-induced brain injury, rebuilding her memories piece-by-piece. Similar experiences with impairment proved generative for dozens of the nearly 100 artists in the show, among them Beverly Buchanan, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Tishan Hsu, and Juanita McNeely.

After the first section, the show is arranged both thematically and chronologically—which turns out to be as confusing as it sounds. But a strong narrative picks up again in the 1980s, with works on technologized bodies responding to AIDS, cancer, and medical advances. Here, you’ll find Zoe Leonard’s photographs of the mobility devices that belonged to Ray Navarro of the activist group ACT UP, alongside works by less expected candidates. A wall text for a 1986 work by Hsu reveals that, after being diagnosed with kidney disease, the artist was told to hang tight until medical technology advanced. The formative experience is clearly reflected in all the abject cyborgian canvases he has been making in the decades since. Nearby, David Hockney’s Breakfast with Stanley (1989), a grid of black-and-white printed sheets, reminds us that the artist, after losing his hearing in 1979, liked to send his friends drawings via fax machine—what he called the “telephone for the deaf”—soon concocting elaborate collaborations with the tool.

The show’s breadth is at once its strength and its weakness. It is heartening to see attention paid to the central, generative role that impairment has played in art history and in all creative endeavors. The curators, Jill Frank and Isabel Casso, made so many discoveries of the sort that I wondered if the trove might be bottomless.

But there’s a delicate balance between expanding a concept and diluting it until it becomes meaningless. Maybe all artists will have experiences with disability, but their experiences—lived and artistic—vary wildly. I found myself wondering how certain artists responded when invited to show in an exhibition with the word “disability” in the title. Maybe the tides are finally changing, but not everyone who experiences impairment identifies as disabled.

The difference does matter, in part because claiming the word is a way of refusing the idea that “disabled” is a shameful thing to be, and because the shared language helps us form a coalition (similar to the kind galvanized by reclaiming words like “queer”). It also matters because it points to the ways that certain structures—inaccessible buildings, unaffordable healthcare, polluted water and air—cause and exacerbate disability unevenly: uniting under the banner “disabled” frames impairment as a political issue, while specific diagnoses speak only of an individual’s body. And it matters because I can’t imagine a show like this show would have ever existed if not for the artists who so boldly gave language to disability before the art world was listening—exhibiting artists like Carolyn Lazard, Park McArthur, Christine Sun Kim, Constantina Zavitsanos, Riva Lehrer, and Joseph Grigely. (I’ve tried to help by recording it all in writing.)

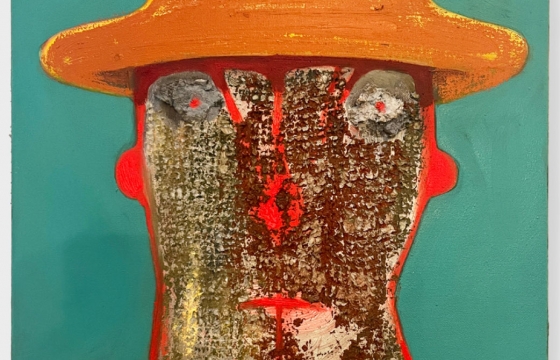

Still, the strongest works in the show are those that allow disability to transform the ways impairment generates new ways of working and being. Contrast these with works that instead take disability as only a subject, which are not always anti-ableist. In one pairing (and one pairing alone), the show acknowledges such tensions: Sophie Calle’s The Blind (1986) is shown alongside Grigely’s retort, Postcards to Sophie Calle. (1991). In a series of questions, the deaf artist gently and incisively critiques the ways that Calle turned the experiences of various people, blind since birth, into an inspiring story that was “not so much the voices of the blind as the voice of Sophie Calle.”

“For Dear Life” is at its best when it does the work of calling people into the coalition. A section framing substance abuse disorders as disabilities invites solidarity across conditions. A 2002 self-portrait that Nan Goldin took while undergoing in-patient treatment for opioid addiction features alongside a wall text detailing how, in 2018, she wrote about her experience for Artforum. After receiving an outpouring of responses, Goldin realized for the first time that she was not alone. She found a community, and started the activist group P.A.I.N., which has since succeeded in having the Sackler family named removed from numerous institutions. It’s a powerful story about how breaking the silence and bucking the stigma is the first step toward forming a community—and then a coalition.

“For Dear Life” is major for the way it highlights the massive role that impairment has played as a generative force in contemporary art. Its flaw is its methodological identity crisis. The show seems to attempt both narrating the historical lineage that gave rise to the contemporary, decidedly politicized disability arts movement; and making a theoretical argument that disability is everywhere—as a bodily experience, but not necessarily a politic. In being both history and theory, it is also kind of neither. One could walk away from the show with the erroneous impression that the artists included all share a language and an ethos. Still, the lineage it charts is humbling and galvanizing.