It’s silly to try to explain David Lynch’s films, since they are designed to induce confusion, but that hasn’t stopped people from seeking answers. Keenly aware that viewers wanted clarity, Lynch once wrote a list of 10 “clues” to accompany the DVD release of his 2001 film Mulholland Drive. Discovering the true meaning of each clue ostensibly unlocked the film’s mysteries; the first stated that two clues were revealed before the opening credits even rolled.

I spent hours puzzling over that first clue as a teenager, rewinding and rewatching the first few minutes of Mulholland Drive again and again, before realizing, as an adult, that there was nothing to discover here at all—the film’s riddle could not be cracked, even with Lynch’s help. Likewise the rest of his films and TV series, from his 1986 feature Blue Velvet to What Did Jack Do?, a 2017 short in which Lynch himself interviews a capuchin monkey who may have murdered someone.

A lopped-off ear, animated bunnies, a deformed (and possibly inhuman) baby, a bottomless blue box: these are all weird beings and objects that signify just that—weirdness. Lynch showed that life was fundamentally enigmatic and therefore impossible to fully understand. The best we can do is take all that peculiarity as a given and buckle in for the ride.

But might I suggest that there is, at least, a path toward understanding why Lynch wanted to represent the world in this way? For that, I’d direct you to his paintings, which he steadily produced alongside his films for decades in what he called his “art life.”

I’m not saying his paintings are better than, or even as good as, his films. There are cases where I agree with critic Roberta Smith, who once wrote, more than a little harshly, that Lynch’s paintings are “familiar, unoriginal and slick.” Yet there are many more cases where I think his art is funny and charmingly off-kilter, too. At the very least, his art is worthy of attention because it offers insight into why Lynch, a painter by training, ultimately moved his sorcery to the silver screen.

It’s not difficult to find thematic ties between his film and his art. The subject of his 1988 painting Shadow of a Twisted Hand Across My House furthers the themes of Blue Velvet, his 1986 film about a young man drawn into the criminal underworld of a quaint North Carolina town. The painting portrays those familiar elements of white-bread suburbia: a little house with a yard beneath a cloudless sky. Yet the skies are black, not blue, and there are no carefully manicured grasses, no green trees, no kids playing around. Instead, there’s a giant hand-shaped tree that seems ready to crush this home in its fingers. Just like Blue Velvet, the painting exposes the seamy underbelly of small-town America.

Characters from his films also recur in his art. The horrifying infant at the core of Eraserhead was sketched by Lynch well before he even completed that film in 1977. A version of the mask-wearing “jumping man” character from his film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, Lynch’s underrated 1992 prequel to his TV series Twin Peaks, seems to show up again in Ant on My Arm, an undated piece that appeared in Lynch’s 2022 Pace Gallery show.

Lynch obsessives will divine other connections between his artworks and his films, but that’s not what makes these works interesting. What is notable, instead, is Lynch’s art-making process, which privileged a handmade aesthetic that wasn’t always so obvious when he was behind the camera.

I have a feeling that for Lynch, the act of painting every day provided an activity that was more tactile, more physical than directing films. He larded all his surfaces with lumpy, indistinct matter that was never disclosed in the checklists for his shows. I asked him about this when I interviewed him in 2018, and he slyly evaded my question, saying only that he used glue, paint, and, naturally, ashes—he was a habitual smoker. He frequently spoke of the chunky admixture, which often combined dried paint pieces with wet acrylic, as an example of “organic phenomena.” He seemed fascinated by the possibility of wielding those “organic phenomena,” as though he were a medium transmuting invisible forces into art.

It’s hardly surprising to learn that Lynch was drawn to art by Robert Henri’s 1923 book The Art Spirit. He was still a high schooler when he read Henri’s book, which suggested that art could help people discover blinding forms of creativity, becoming “clairvoyant” along the way. Before he tried to reach other realms using cameras, he did so using a paintbrush and a canvas.

You can see him trying to summon the spirit world early on, in works such as an untitled piece on paper made between 1965 and 1969 that figured in his 2014 Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art retrospective. Against a black void, there’s a big spray of crimson—a cascade of blood, perhaps—placed beside a gaping maw. It’s as though this red flow is something malevolent and alien, a force that cannot be stopped.

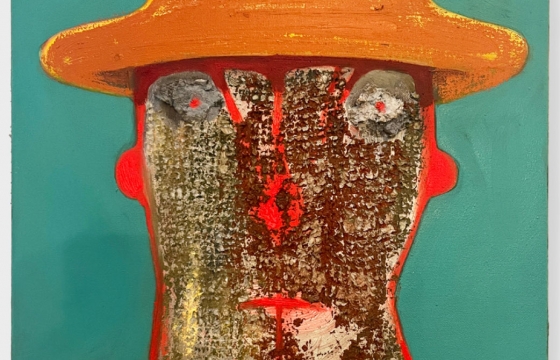

Lynch also produced figurative paintings during the years after he studied at PAFA, where he was enrolled between 1966 and 1967. These works, too, are largely set in darkness, this time with more obviously delineated creatures: women whose mouths curl into knives and machinery parts, men with distended arms. As these figures move in and out of the shadows behind them, one can sense Lynch trying to conjure that which cannot easily be seen.

One joy of these works is that they are unclassifiable—they do not fit cleanly within any art-historical rubric. (Robert Cozzolino, the curator of the PAFA retrospective, wrote that Lynch’s paintings share something in common with those of postwar Los Angeles artists such as Llyn Foulkes, who dabbled in a similar kind of unbridled strangeness. Yet the comparison falters because Lynch was working all the way across the country, in Philadelphia, and anyway, Lynch claimed to know virtually nothing about art history.) But yet another joy of these Lynch paintings is that they refuse to cohere.

It’s abundantly apparent that, for Lynch, film provided a way of turning these oblique images even odder. Six Men Getting Sick, his 1967 painting displaying exactly what his title suggests, was set in motion when Lynch projected pictures onto it and filmed the results, effectively constituting his first movie. Gardenback, his 1968–70 painting of a humpbacked figure, shares its name with an unrealized film written by Lynch that was to center around the notion of cheating.

Film scholars tend to reference these paintings as a transfer point in Lynch’s oeuvre, as though they were insignificant works that paved a path toward greatness. I’d argue the opposite: paintings like Gardenback already functioned well as a means of channeling other universes, and Lynch simply continued that activity with filmmaking.

I find it useful to think of his features as filmed art installations, full of individual works enacted by performers. That was certainly the case with Eraserhead, at least. Lynch personally crafted a number of the elements seen in the film—the highly stylized lighting fixtures recall the unusable lamps he later showed as sculptures—and he continued to produce art during Eraserhead’s production, with drawings made to help develop the images he wanted to see into reality. Directors commonly storyboard sequences before shooting, but these drawings don’t describe what he ultimately shot. They were more like sketches produced in advance of an ambitious painting, and that painting, in this case, was a feature film.

There’s a wonderful photograph shot during the production of Eraserhead in which Lynch can be seen making a drawing between takes. The actor Jack Nance can be seen here, awaiting another take, but Lynch doesn’t seem much interested in sketching him. Instead, Lynch’s pencil drifts along a paper, forming a string that winds around a hand holding a gun. Notably, Lynch has rested his paper atop a clapboard, using the tools of film production to support his art.