Skeleton Crew is 10-year-old me’s favorite Star Wars show. The series follows four children who escape the boring planet of At Attin in search of adventure only to try to get back to it chased by a space Long John Silver and a cohort of bloodthirsty, gold-hungry pirates.

The premise itself is charming enough, but really it’s the design of Skeleton Crew’s world that is responsible for its real magic. Every aspect of the production design has been carefully developed to serve a single objective: to view the galaxy far, far away through the eyes of a kid who sees it for the first time.

The show is filled with details that make you feel like a kid watching Star Wars. Like its protagonists, four space Goonies. Or the instantly iconic spaceship they find buried in their neighborhood’s backyard forest, which takes them to a pirates’ cove in the middle of a nebula (one that looks like the cosmic version of a bay somewhere “deep in the Caribbean”).

There’s also a fantastic alien owl who is an astronomer, a robotic first mate with a creature living inside his head, an ancient booty in the heart of a booby-trapped secret maze, and Jude Law just being Jude bloody-damn-hot Law chasing a legendary treasure planet. Ultimately, though, it’s the way the production team built this new (old) world that made it all click as an experience that struck my 8-year-old kid and my grown-up self with a 1.2-gigawatt lightning bolt of happy feels.

That energy came from the vision of its co-creators, Jon Watts and Christopher Ford. It permeates every single set, creature, light source, music note, camera move, edit, and color-grade choice in this show. In my opinion, Skeleton Crew is more worthy of its opening Lucasfilm logo than The Mandalorian or Andor. Because, while I love those shows too—Andor remains adult me’s favorite Star Wars story—each Skeleton Crew episode has the ability to instantly fire up the warm popcorn aroma and static electricity of a theater full of people waiting for the first notes of a John Williams or Alan Silvestri score.

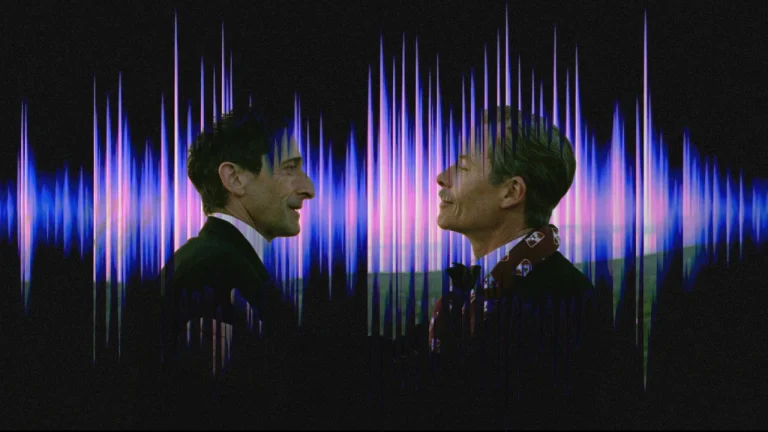

“That vision started from a very simple place: We wanted to tell the story about a group of kids who didn’t know much about the Star Wars universe getting lost in the Star Wars universe,” Watts tells me during a video interview. The director—known for the three Marvel Spider-Man films, Homecoming, Far From Home, and No Way Home—says, “When you decide you’re going to tell this story from a kid’s point of view, it affects everything aesthetically from that point on.” Ford, who previously worked with Watts on Spider-Man: Homecoming, agrees: “What is the feeling? The feeling is being 10, yearning for adventure, and then suddenly being in way over your head.”

Watts and Ford’s first directive to the design team was to create things that might feel overwhelming to a kid. “Like how to scale things so the kids feel small in a much bigger world; how to make the ship feel really unwieldy and dangerous and hard for them to fly,” Ford explains. “That was sort of our entry point and kind of the simplest perspective that you take on those decisions.”

Watts brought on Oliver Scholl, who worked with him on Spider-Man: Homecoming, as Skeleton Crew’s production designer. He remembers that he didn’t hesitate at all, not only because it was Star Wars but because he loved that vision. “The kids are standing in for us, re-exploring the Star Wars universe from a young perspective,” he tells me during a video call. It gives everyone the opportunity to frame a mythology like we experienced it in the first place, without complications. “It was exciting because it’s not a serious or gloomy film. It’s fun storytelling and entertainment.”

Designing a Familiar feeling

Working with Watts; Ford; Lucasfilm’s executive creative director, Doug Chiang; and Industrial Light & Magic’s chief creative officer, John Knoll—plus The Mandalorian’s co-creators, Jon Favreau and Dave Filoni—Scholl embarked on a similar journey of discovery, which started at the kids’ world, At Attin.

Watts and Ford were excited about exploring the middle-class aspects of Star Wars, unlike the usual focus on the extremes of the galaxy. Lucasfilm’s Chiang says that before the project took off, Filoni and Favreau told him about Watts and Ford’s “domestic” Star Wars-through-a-kid’s-eye pitch. “They asked me to do some art for it, basically to frame it,” Chiang says. “Sort of without really knowing the context of what’s important, we did a bunch of art to show a residential suburban Star Wars with these kids going on this journey. And that pitch art was what started the project.”

When the preproduction started, creating this suburb was the first order of business. “Star Wars and other movies of the time—like Blade Runner—had a specific language set up for urban environments,” Scholl tells me. They were more fantastical than realistic, like Coruscant, the world city capital of the Republic that we saw in the Star Wars prequels and Andor, a TV show that Watts found very interesting because it also showed mundane places in this galaxy. “We wanted to capture the spirit of being in a safe but boring place, and wanting to escape from school, parents, and homework,” Watts says—a middle-class suburbia that is the only home they know before getting sucked into a chain of events that take them to outer space for the first time ever.

To convey this, they designed two main areas in At Attin: the city center and the suburbs. “The city center is based on American city layouts,” Scholl says, “but it also incorporates elements from brutalist Soviet Eastern European and Japanese urban planning studies. This stiffness and rigidity fit the story, as the city has been set in its ways for a long time.” For the suburbs, where the kids grow up, they wanted to create Star Wars-like middle-class houses. The showrunners wanted to evoke “a Goonies feeling.”

Initially, Scholl says, they went too far with the Star Wars sci-fi element, and the houses didn’t capture what Watts and Ford wanted. Then they took a different approach. They set the houses in the middle of rolling hills and forests, inside a cookie-cutter urban development that feels very much like ’80s American suburbia. “Our touchstone was Steven Spielberg’s work on ET and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, which depicted ordinary life and family love, and then transform that into Star Wars,” Chiang explains.

The resulting vehicles, droids, costumes, and interiors were developed to evoke Earth’s objects. “The magic of designing for Star Wars,” Chiang reminds me, “is that it is 80% grounded in our terrestrial reality.” Take the city’s school bus, whose bench seats are identical to those found on a school bus today. The designers simplified the exterior by keeping it a clean box shape. Then they add two of these buses’ seats in tandem, creating a sort of “twin bus” effect.

“By taking something familiar from the inside and twisting it slightly, we repackage it to create something fresh and new, which the audience immediately understands as a school bus because they’re familiar with the shapes and layout,” Chiang says.

This approach was pioneered in the early days of Star Wars, when designers repurposed model parts and shapes from the real world to create places and vehicles. Boba Fett’s spaceship design, for example, was famously taken from a modern street lamp. “We didn’t just ask what suburbia would look like. Instead, we defined the shape language to ensure it spoke to Star Wars while also informing the world we were creating,” Chiang says.

When it came to designing the houses of At Attin, the team arrived at a triangular rooftub structure that created slopes when viewed from a distance. Chiang says that the repetition of these roofs on the tract homes resulted in distinct shapes and silhouettes. Though the homes feel different from each other individually, in aggregate they feel familiar.

The same is true for the home interiors, which have that ’80s feeling fused with Jetsons’-like sci-fi details. These were all built as one real full-size set which, as Knoll tells me, was partially rebuilt and redressed through the production to depict the different-yet-similar homes of the protagonists.

“It fits right in the production design of the show. All the houses were meant to look like they were kind of built in one era with one style, and there are some smaller houses and bigger houses,” Knoll says. “Fern lives in a more exclusive neighborhood where the houses are bigger, with an upstairs with a larger balcony, but it’s still very much the same style of architecture and most of the pieces are shared between them.”

The fifth character

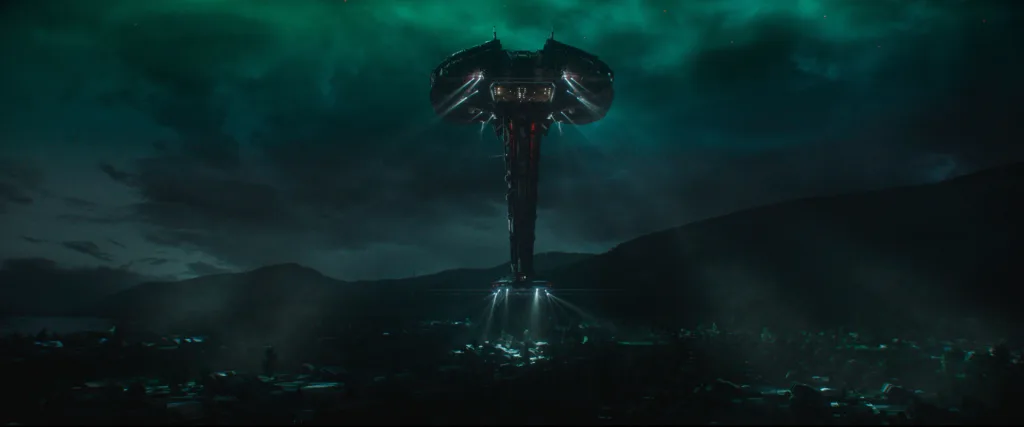

While At Attin is the center of the storyline, viewers barely see it after the kids find the buried spaceship that becomes their Millennium Falcon. Called the Onyx Cinder, the spaceship is a mystery that is key to solving what’s going on in At Attin.

Scholl tells me that the Onyx Cinder was fun for him to design because of his background as a concept artist. “Everybody wanted to do it, and we all had our ideas of what it needed to look like,” he says. There were many conversations between him, Chiang, Ford, and Knoll about how it should look. The ship is not what it seems at the beginning. (Spoiler alert: It’s encapsulated in a menacing clunky shell that hides a really sleek vehicle that gets revealed in a critical moment of the series.)

“The key for its first design was the ironclads,” Scholl says. These were the first warships that were steam-powered and protected by steel or iron armor, first employed during the American Civil War in 1862 to easily destroy wooden warships. “Doug and I wanted to do something a bit more intricate in the beginning,” he tells me, but then they kept looking at the ironclads and their brutal simplicity. They also needed the Onyx Cinder to look like it came from a different era, so this starting point was perfect for it.

It also had to call back to Star Wars elements. The asymmetrical position of the cockpit, for example, connected it to the design of the Millennium Falcon. The surface of the clunky, armored Onyx Cinder is textured like Han Solo’s ship too, with lots of tubes and boxes. And there are typical elements of other ships, like the gun turrets and the loading ramp.

The ship’s interior feels different from the exterior. While it’s covered in dust, skeletons, old pirate gear, and roots from wild plants that grew after the ship was buried, its design is surprisingly smooth and futuristic. The cockpit—which looks like Queen Amidala’s Naboo Royal Ship from the prequels—tells the story of its true nature: This is actually a ship from the era of the Old Republic.

Like the Falcon, the Onyx Cinder is its own character, which evolves with the show. For most of the series, it’s this clunky, massive vehicle that seems to be falling apart. “Every time it goes into a hyperjump, it will leave dust and branches behind it. It’s really funny,” Scholl says, just like when the roadrunner runs off leaving a cloud of dust behind him. But in one crucial point in the series, it sheds its armor that surrounds it as well as its frontal engines, revealing a smooth, blueish-black wedge-shaped body with just four engines on the back. It is like a butterfly coming out of an ugly caterpillar, perhaps a metaphor of the four kids coming of age at the end of the series.

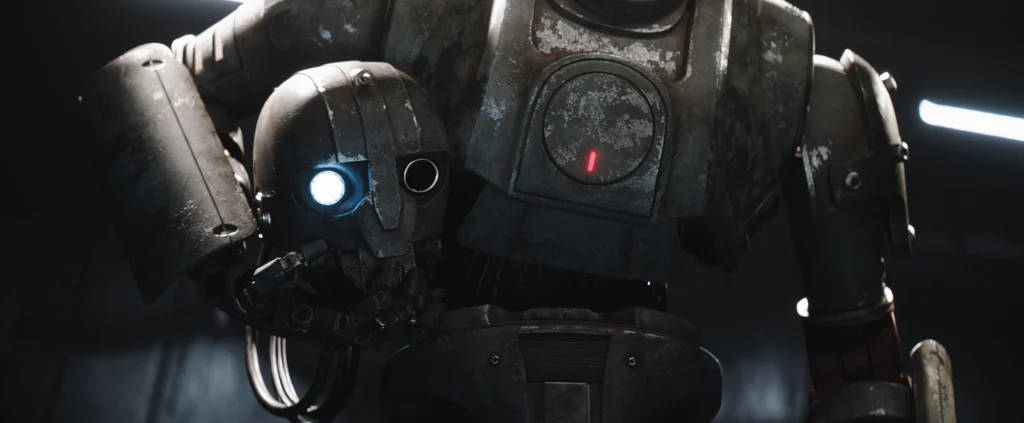

The Onyx Cinder also comes with another iconic character: a robot called SM-33—or “thirty-three,” as the kids call him—which happens to be the ship’s First Mate. Found “dead” on the floor, this humanoid android’s design makes it look like a very tall, menacing version of C-3PO voiced by British actor Nick Frost. The android is not alone. Inside of it lives a little hamster-like animal that appears through the cavity of one of the eyes SM-33 is missing.

SM-33 is an example of how production design adapts to the evolving vision of a series. Knoll tells me that the little critter wasn’t going to be a big part of the character but Watts ended up really liking him. “The first animations that we did had a lot of character to it and it started becoming the showrunner’s favorite character,” he says. “We get these periodic updates where they asked to put the rat in some scenes.” Its presence became so significant that my son and I thought he was somehow controlling the robot. In fact, this was sort of left a little ambiguous by design, Knoll confirms. For example, “whenever ‘thirty-three’ starts to glitch out and has trouble remembering, usually the rat rolls out somewhere, sort of implying that something is happening.”

Into the wild

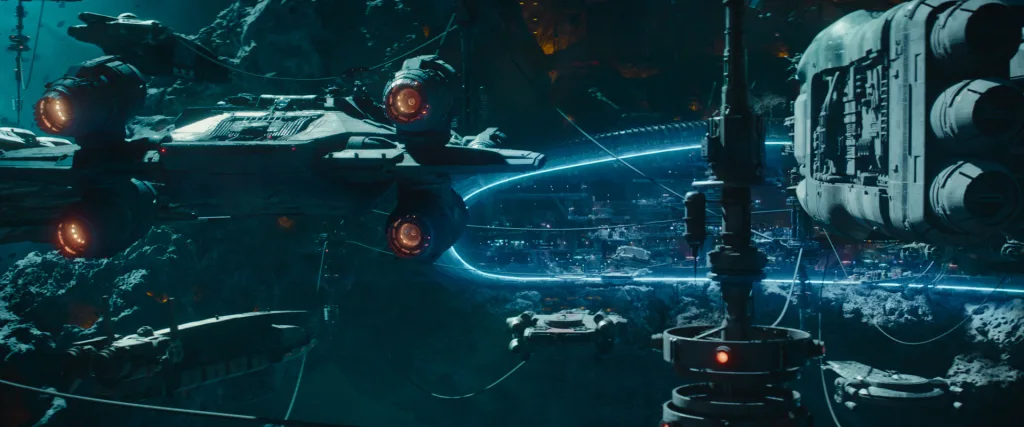

The Onyx Cinder takes them through many worlds, including a bizarro version of At Attin, in which we see exactly the same structures after some short of Mad Max apocalypse. But the most impressive place is the pirates’ cove, Port Borgo, where the kids arrive after they leave their home planet.

Lucasfilm always tries to give all the designs—whether it’s a location, a building, a character, a creature—a unique personality, Chiang tells. Since the adventure of Skeleton Crew is that you’re visiting all these exotic worlds, he says, they wanted each of these locations to be distinct, and nowhere this is more true than in Port Borgo.

“Port Borgo is one of the most fun design challenges because we’re taking the convention of a pirate’s cove and we are turning it on its head,” he points out. It’s a pirate port floating alone in space, which is a weird concept because it’s not on a planet. It’s a set of floating asteroids that serve as islands, set against a bright turquoise and aquamarine nebula. “You understand what it is when you look at it instantly,” he says. You can see the shape, which looks like a pirate’s cove. You can see the way the shapes are lined up. They’re very much like ships docked in the bay.”

The contrast of the color palette is key here too. We are going from the subdued pastels of At Attin—indicating that the kids’ home world is the epitome of a beige existence—to these black islands framed by a bright blue nebula. “Color palettes are one of the main tools we use to make things distinctive,” Chiang says.

“One of the things we always try to achieve is that Star Wars is about design clarity,” he continues. “It’s about designing things that are easy to read and understand very quickly. But then underneath that, we have many layers of history.” The history is the homework that they do to make the designs authentic, everything cohesive and believable.

The physical element

Part of this process of making things believable is to make things physical. Unlike with the Star Wars prequels, which relied on blue screen and computer graphics, many of the elements in Skeleton Crew were physical objects and many of the effects were practical and not done in 3D. This path—which was fully embraced by Andor to make its world building feel so real—was especially important for this show because of the kids. As Watts and Ford points out, they were reacting to physical things all of the time. “Their emotions on camera were genuine,” Watts points out.

This happened in subtle ways, like the scale of the sets. The Onyx Cinder, for example, was a full physical set. “It’s not like the cockpit was on one stage and the mess area was somewhere else,” he says. “It was all kind of laid out and connected so you could do shots of a character walking all the way from the cockpit into the engine room and then over to the mess.” For the external shots, they also built a three-foot-long miniature of the ship, which is what you see in the first few episodes. “All those shots approaching the spaceport, for the most part, were all miniature shots.

Sometimes the ways they made the kids react in awe or in horror weren’t as subtle. SM-33 was a great example of this. Legacy Effects—the company that built it—constructed three versions of the droid. One was a partial suit, another was a digital model for the fighting sequences, and the third was a full animatronic puppet. They used the latter for when the kids first encountered the robot. When they saw the robot, they were in awe. Then, in the same scene, when they are trying to turn it on and it suddenly comes to life, it makes them jump. Those were genuine reactions to something they hadn’t seen before, which links directly to the Amblin tradition.

In The Goonies, a lot of the practical stuff was never disclosed to the kids. The biggest example was the reveal of the ship at the end, when they made them jump into the water. As actor Josh Brolin explains in this video, when the Goonies come out of the water in that big scene, they had never seen it before. Their faces of awe were real.

“There are certain things where we would show them ahead of time so that they wouldn’t get scared,” Watts recounts. “But we tried to save the overall experience moments. There’s a lot of moments in the show that are the first take, where the kids are doing all this stuff for the first time.”

That Amblin magic works

Which takes us back to Watts and Ford’s original vision: Showing the Star Wars universe through the eyes of a kid who has never seen it before. I think Skeleton Crew struck me so hard because it has recaptured that joy, the long gone sense of awe of watching films, reading comics, and playing video games as an ’80s padawan. And it connects with me as much as it connects to my 8-year-old, who watched each episode with the hunger and fascination with which he watched Indiana Jones, Back to the Future, Gremlins, and, of course, Star Wars itself.

Sadly, its sad ratings didn’t match all of this fun. According to Nielsen’s streaming data from December 2 to 8, the first two episodes of Skeleton Crew premiered with the lowest viewership of any Star Wars series in its initial week. It’s too bad. In times like these, it seems to me that we need more fun Amblin magic rather than the darkness of the many dystopian shows and films now populating the streaming services. Like Tom Waits sings, I just don’t wanna grow old.

So do yourself a favor and go watch all Skeleton Crew episodes on Disney+ right now.