The city of Los Angeles has rightfully gripped the nation’s attention this month as wildfires rage on. While the devastation induced by our changing climate demands superhuman effort to squelch it, the transportation sector (stubbornly responsible for the greatest share of U.S. emissions) is ironically observing a significant milestone. January 24, 2025, marked the centennial of the implementation of the Traffic Ordinance for the City of Los Angeles. This 35-page bureaucratic document redefined the use of America’s streets, tailoring them to the benefit of the automotive industry.

American streets were once dominated by people. A documentary travelogue of New York City captured by Scenska Biografteatern from 1911 is crowded with pedestrians crisscrossing streets in their daily routines. Trollies, carriages, and the occasional automobile jostle by, unhindered by traffic signals or centerlines. To us today, it can seem chaotic, but the pace of the street is slow, and people navigate each other with fluency.

San Francisco’s A Trip Down Market Street, shot just a year before the 1906 earthquake, shows the view from a streetcar, picturing the Ferry Building at the street’s end obscured by intertwining streetcars, horses, bicyclists, cars, and people. Pedestrians stand undaunted in the center of the street, waiting to board the slow-moving streetcar. A boy playfully darts in front of the train, as if he is challenging it to a game of tag. Growing up in American cities meant playing in the streets, even in the country’s most dense neighborhoods.

Back then, people shared the roadway with streetcars and bikes. In the early 1900s, Los Angeles had the most extensive electric streetcar system anywhere. From Minneapolis and Chicago to Washington D.C. and New York City, bicycles were used by women and men commuting to work in the 1890s. And they were not alone. As Evan Friss chronicles in The Cycling City, people rode bikes in U.S. cities as much as they now ride in Amsterdam and Copenhagen, the best cycling cities in the world.

This was all before the Los Angeles Traffic Ordinance was passed. The Ordinance was written by Miller McClintock, then a doctoral student of municipal government at Harvard University, who was recruited by a champion of the automobile industry, Paul Hoffman. Hoffman had dropped out of the University of Chicago to sell Studebakers at 18-years-old. At 33, he was close to making his first million dollars in the industry and had been appointed chairman of the Los Angeles Traffic Commission—a body responsible for regulating streets. For the first time, the Ordinance prioritized cars on the city’s increasingly congested roadways. It quickly became the template for the country.

With a contemporary eye, the provisions created by the Ordinance may seem more logical than they were to city dwellers at the time. Historian and author Peter Norton has spent his career researching the automobile era and has well documented it in his books Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City and Autonorama: The Illusory Promise of High-Tech Driving. Norton has scoured letters to the editors of local newspapers, written by everyday people who passionately argue for their place on American streets, just as it was being usurped. With the anniversary of the Los Angeles Traffic Ordinance approaching, I interviewed him to understand its significance.

Norton says that sharing streets always required negotiation, but before the Ordinance, “the pedestrian had the absolute right to the street, to stroll into it at any point, and to cross it anywhere she chose . . . even a child had the right to the street.” This was a social norm, but as Norton’s research suggests, it was also defended by judges in U.S. courtrooms throughout the country. For example, in Fighting Traffic, he cites a Philadelphia judge who, in 1924, lectured drivers in his courtroom, saying, “It won’t be long before children won’t have any rights at all to the street.” He determined that motorists deserved restraint if they could not assume the responsibility of ensuring children’s safety and resolved, “Something drastic must be done to end this menace to pedestrians and to children in particular.”

It may be hard to imagine today, in a country where the vast majority of people commute by car, but in Los Angeles and many U.S. cities in the early 20th century, most people didn’t use cars to get around. The majority of American women didn’t get driver’s licenses until the 1960s, and if a family owned a car, men usually monopolized the use of it. People generally walked, rode streetcars, or biked. Norton argues that while the transition to auto-dominated streets is often seen as the arc of progress stimulated by consumer demand, it was actually a well-crafted campaign produced by those with an interest in selling automobiles.

The Los Angeles Traffic Ordinance changed who was prioritized on city streets. Between 1914 and 1922, the number of cars on the streets of Los Angeles quadrupled. To continue to boost sales, the automobile industry required an edge over its competition with the streetcar and one of its advantages was speed. At the time, a streetcar traveled at approximately 10-15 miles per hour, and without dedicated lanes, at even slower speeds when they were blocked by cars. In the Ordinance, McClintock imposed a 35-mile-per-hour threshold almost everywhere except for a few limited cases. But 35 miles per hour was unprecedented in the early 20th century. According to Norton, most cities held motor vehicles to 8–10 mile per hour speeds. In his words, the automotive industry realized that, “If drivers cannot go faster than a streetcar, then they’re not going to buy a car, especially if they have a streetcar service available to them . . . So, we cannot afford to let speed be the culprit in traffic safety.”

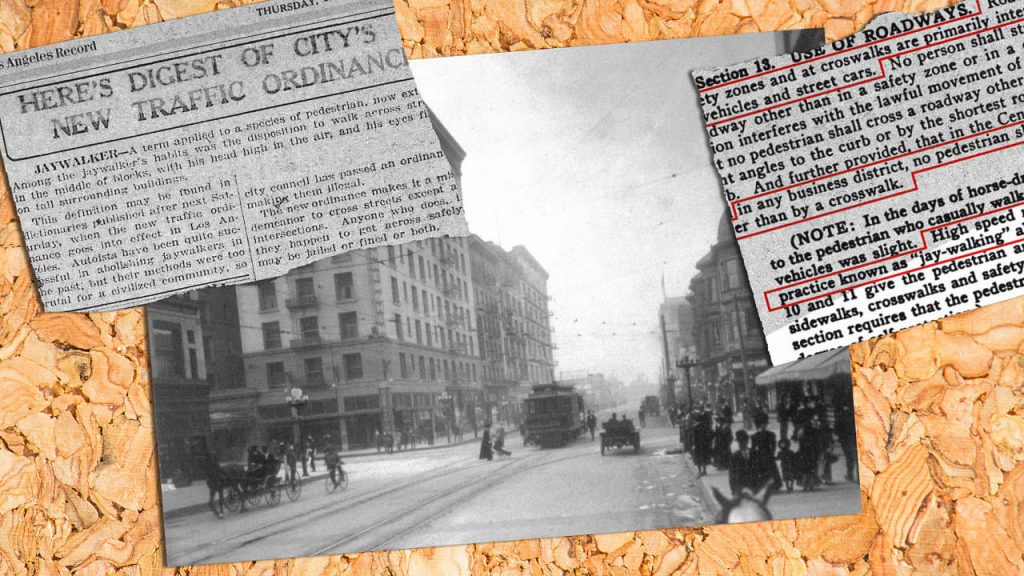

Instead of focusing on speed, the Ordinance decried recklessness. Most importantly, it pinned “reckless behavior” on pedestrians rather than speeding cars. The Ordinance calls out “jaywalkers,” criminalizing pedestrians who do not “obey signals” or who walk outside crossings. “Jaywalking,” once used as derogatory slang, was employed formally to fix attitudes against wayward pedestrians. McClintock writes that, “High-speed motor traffic makes the practice known as ‘jay-walking’ almost suicidal” instead of questioning the imposition of hurtling motor vehicles on streets occupied by people. As Norton suggests, “You could use exactly the same facts that he’s using to say that driving at speed is homicidal.”

In the 1920’s, traffic injuries and fatalities were climbing. In his book Fighting Traffic, Norton observes that between 1920-1929 motor vehicles killed more than 200,000 people in the United States (approximately four times the death toll of the previous decade), long before most adults drove. Horrifically, many of those killed were the most vulnerable, including the elderly and children, especially in dense cities where the casualties were the highest. The public was naturally concerned about safety and the Ordinance addressed their concerns about the dangers of mixing cars and pedestrians, saying, “These conflicts account for the great majority of the accidents and fatalities in Los Angeles and in every other city.”

However, the Ordinance co-opts safety as a tactic to make more room for cars. For the “control and protection of pedestrian traffic,” McClintock suggests restricting pedestrians to striped crosswalks, raised platforms on wide roads called “safety zones,” and even tunnels created to protect schoolchildren from motor vehicles. He overlooks the social life of the street and even requires that pedestrians “not stop or stand on the sidewalk except as near as physically possible to the building line” to remedy what he calls the “too frequent congestion of pedestrian traffic by casual groups gathering on the sidewalk.”

The Ordinance didn’t change city streets by itself. It was accompanied by a clever public relations campaign targeted at cultural norms and advanced by E.B. Lefferts, president of the Automobile Club of Southern California. Lefferts designed the campaign to succeed where other cities had failed. As Norton documents, Lefferts told an audience at the Chicago convention of the National Safety Council that the Ordinance worked because “We have recognized that in controlling traffic, we must take into consideration the study of human psychology, rather than approach it solely as an engineering problem.” As Norton summarizes, Lefferts’ tactics aimed to make people “feel embarrassed, perhaps ashamed . . . to feel the sting of ridicule.”

Radio broadcasts aired a public education campaign about behavior on the street, the Boy Scouts were deployed to issue cards to offenders, letting them know they were “jay-walking.” Ultimately, the police were emboldened to blow whistles at anyone attempting to cross the street against the signal or outside marked areas—shaming them into submission. Norton discovered multiple cases where people were humiliated by police officers who “picked up pedestrians . . . (mostly women) and put them on the curb.” Those who protested this new treatment were arrested.

The Los Angeles Traffic Ordinance established that streets would not be shared but dominated by cars. It was essentially a land grab. Once the roadway was secured for the benefit of motor vehicles, they were the heavyweight champion on streets that had once been for everyone. The Ordinance required that pedestrians were “subject to the same directions and signals as govern the movement of vehicles” without acknowledging that they were exceptionally vulnerable. Facing the mass of a speeding car, no other users of the roadway could compete in the physical battle to claim the streets.

By upping speeds on American streets and designing them for accelerating cars, motordom prevailed. Even today, Norton says, “we still hold the view that you try to make fast driving safe instead of signaling to drivers that they need to be paying attention and slowing down.”

The logic of the Los Angeles Traffic Ordinance soon made its way into the Model Municipal Traffic Ordinance, which passed in 1928 under the direction of Herbert Hoover, then the Secretary of Commerce, in close consultation with the automobile industry. It became the template for similar ordinances throughout the country. As Norton maintains, “Just about everywhere you go when you’re dealing with the local rules . . . they’re descended from this ancestor, the Los Angeles Traffic Ordinance.”

McClintock went on to author a proposal for “foolproof highways,” in the mid-1930s, promising safety through gradual turns, grade separations, and streets for the exclusive use of the automobile—again with the promise of increasing speeds. Those highways would ultimately bring more cars into the hearts of urban areas, with a growing human toll. Outpaced by cars, and bullied to the margins, bicyclists also lost their place on the road. Eventually, streetcar tracks were pulled up, some replaced by buses. However, mass transit was increasingly restricted as tax dollars secured by the Highway Trust Fund were unevenly divided by an 80-20 split favoring spending on highways.

Unfortunately, dedicating streets to cars did not guarantee safety. In 2021, more than 43,000 people died on U.S. roads. Cars have become larger, faster, and heavier, making them even more deadly, especially to children. In America, from the time a child can walk until she reaches adulthood, being hit by a car has been the number one cause of death for many decades (surpassed only recently by firearms).

Norton objects to our collective history told as if auto dominance was the inevitable direction of progress. He has uncovered the mass of people who urged the country in a different direction. “It was ordinary Americans from all walks of life, rich and poor, Black, Brown and White, male and female who were objecting to their loss of the use of the street.” Among them was Philadelphian Barnett Bartel who, as the Model Municipal Traffic Ordinance was being deliberated, urged Hoover to protect people on roads. Bartel describes the appalling loss of his sons to what he identifies as “murderers.” Bartel’s 9-year-old was killed on his walk home from school by a truck that jumped the curb on his walk home from school, and his 18-year-old was run over by a car on his bike in a hit-and-run and left to bleed to death.

Bartel was one of many bereaved parents whose letters crowded the local papers. Their protests continued in the 1950s when women-led “baby carriage blockades” obstructed streets so children could play safely outside. Norton acknowledges that “it is incredibly helpful to recover these lost perspectives because then we can step out of the perspectives that we grew up in, and that we were socialized into, and look at them afresh with new eyes and possibly see opportunities.”

As jaywalking laws are repealed in cities and states across the country, as congestion pricing removes automobiles from the heart of the largest U.S. city to pay for transit, as pandemic-era open streets evolve into new permanent urban parkways, and as a new administration hangs its hat on advancing “freedom,” Norton encourages us to reconsider the 100-year history ushered in by the Los Angeles’ Traffic Ordinance. He suggests a new version of our history that avoids the false advertising that Americans have always had a love affair with the automobile. Perhaps with the new space allotted on our streets, and the laws that govern them, we will reclaim the cultural history we gave up and the freedom of choice we once exercised so that at any age, we can walk, bike, and ride where we want to. “If we recover that history,” says Norton, “we empower ourselves in choosing alternative futures.”

This story was originally published by Next City, a nonprofit news outlet covering solutions for equitable cities. Sign up for Next City’s newsletter for their latest articles and events.