It was the year 2000. We survived Y2K and sat at our computers obsessed with a strange new game called The Sims. It was the first game I ever played where the protagonist could be late to work, forget to take out the garbage, or be so preoccupied by the doldrums of life that they might pee themselves.

I, alongside millions, was hooked and could not articulate why.

Born from the mind of Will Wright—the same designer who bucked the industry’s penchant for arcade games for world simulators like SimCity—The Sims is almost as hard to define now as it was then. Is it a virtual dollhouse? A simulacrum of suburban life? A neighborhood of tamagotchis with jobs? An HGTV home improvement show crossed with Real Housewives?

By design, whatever you call The Sims may reflect on you more than it. From its earliest days, The Sims universe has attempted to be anything but prescriptive—right down to its progressive view on relationships without labels or gender expectations. Twenty-five years later, the franchise, now owned by EA, has amassed half a billion players. The Sims 4 came out over a decade ago at this point, but after it became free-to-play in 2022, its popularity ballooned to reach 85 million players, and it’s released 17 expansions that allow people to do everything from arguing over family inheritance to convening a court of vampires.

For the 25th anniversary, I sat down with two creatives that have been with the franchise since the original game to discuss their core design approach of The Sims, what’s kept players obsessed, and why fewer of these little characters are peeing themselves these days.

A funhouse mirror of the world

The Sims may have a quiet premise—create a character and their home, choose a profession, and socialize with neighbors—but nothing about the presentation from there is literal. Through every bit of its art, design, and animation, the world balances the mundane with the zany. That not only brings an element of fun to The Sims; it expands what’s plausible at any moment.

“We definitely talk more about being relatable than realistic, which means that we do lean more dramatic in our acting and our animation,” says Lyndsay Pearson, VP of franchise creative for The Sims. “That’s partially because of the way you play the game: You’re far away [from characters], you need to be able to read it. But also because that supports the world and the stories we’re trying to enable.”

Each gesture of these little characters is exaggerated, as if they’re actors on a stage being read from the audience, even though you’re just sitting at your computer. That ensures that the mundane feels interesting.

“When you’re cooking, or going to sleep, or making up the bed, or doing these life actions, a lot of your players actually want to experience them in this extremely whimsical and playful fashion. Nobody wants to see that in a replica of actual real life the exact same way,” says Nawwaf Barakat, senior animation director for The Sims. “So it needs to be telling its own story every single time. It needs to look interesting the 1,000th time you’ve actually seen it.”

The tone of those moments isn’t merely legible or entertaining; they also highlight the farce, expanding what’s possible in the world.

“We’ve described it as a fun house mirror to the world, where it looks familiar enough that you can relate to it and feel like, ‘Oh, if I if I take out the trash, I understand the chain of events and the rules of this universe,’ but it’s all skewed so that when a giant monster pops out of the trash, I’m not surprised. [The design] explains that these things can coexist.”

Implying so the player can infer

While players enjoy rich, multigenerational stories in The Sims—complete with love, backstabbing, and sudden plot twists—in fact, the design team admits that most of this narrative takes place in your head. “The Sims is really a game of interpretation,” says Barakat. “It’s amazing how much our players will actually fill the stories in themselves.”

A key idea behind fiction, born from The University of Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop, is that the writer should imply so the reader can infer. The Sims is designed to do this across a character’s relationships. The Sims speak in Simlish (gibberish that sounds almost like English). You can broach a topic, like “brag about promotion,” but responses from characters are always in either Simlish or word clouds filled with simplistic, emoji-like images.

Many players try to tell multi-generational stories in the game, and recently, The Sims released an expansion all about death and family legacy. The challenge was about creating an opportunity for these stories without determining the plot ahead of time.

“We added enough conversation dialog choices or enough icons in the thought balloons to get them to think about the character or think about a gravestone, that you could make that story kind of happen,” says Pearson. “So, we have to carve out those spaces, particularly to leave room for that interpretation to say, ‘Oh, this could be them all mourning at a wake,’ but it could also be, ‘They’re all fighting at a wake.’”

These techniques almost sound silly to deconstruct, but they’re also at the core of how iconography and symbology works across culture. There are points where interpretations are shared, and points where they diverge. Everything in between is the fun of criticism IRL—and where the opportunity for differing interpretations around narrative exist in The Sims.

“You see comments online sometimes about how deep our game is, how we thought of everything,” says Barakat. “And we’re like, ‘Wow, we didn’t really think about that!’ It was our players building that story based off of all the elements we provided.”

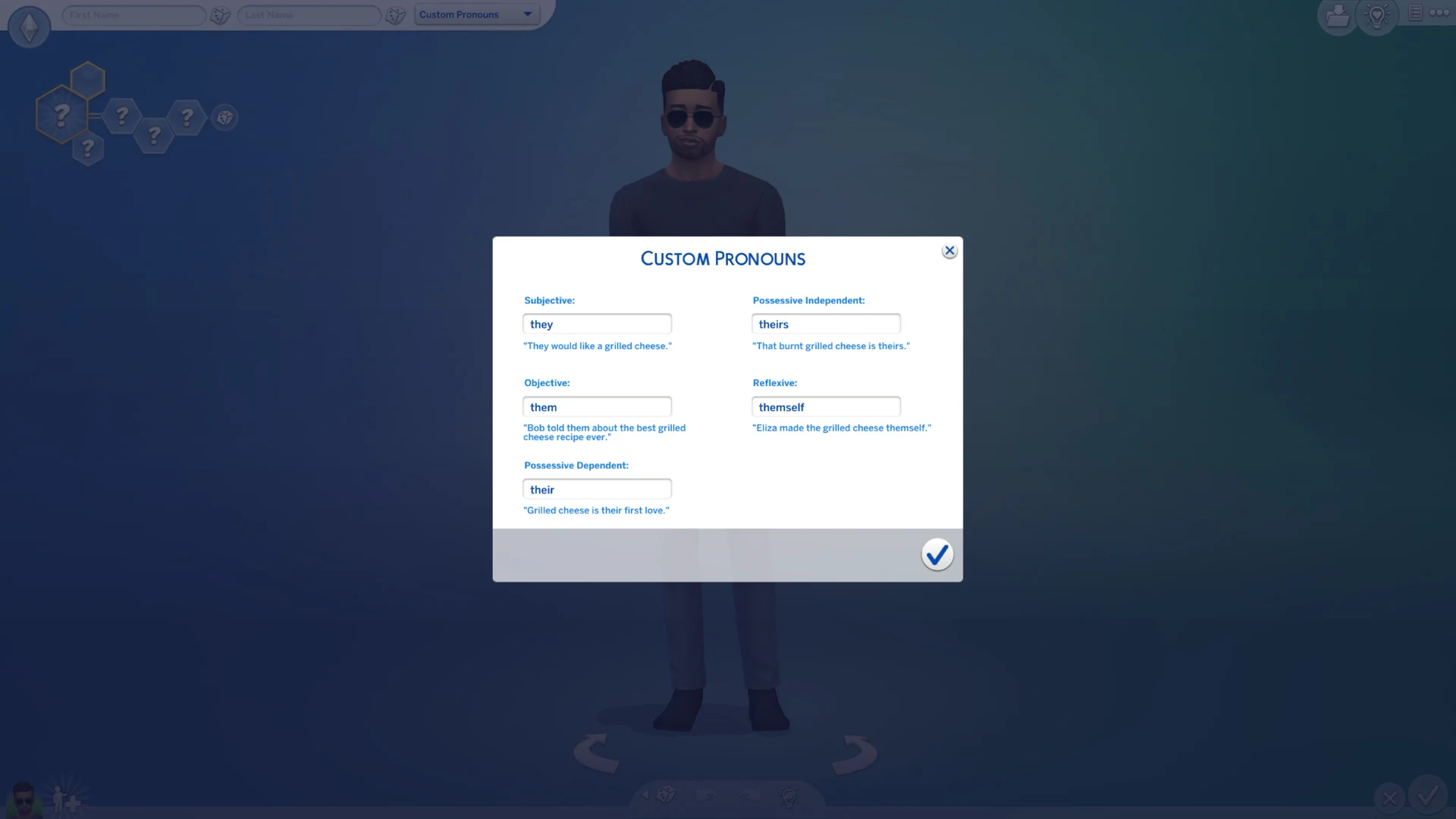

By avoiding labels, not only is The Sims less prescriptive, it is also more inclusive. (You won’t find Republicans and Democrats in The Sims, for instance.) Since the earliest days of the game, relationships spanned gender boundaries without specific labels around status. Today, The Sims 4 does allow players to very deeply specify a character’s gender and sexual identity (and even if they lactate), but still, the way this background plays out in actual game logic can be fluid and, again, unlabeled. Sims may fight, but they don’t judge.

“Is polyamory just the absence of jealousy? Because functionally, that’s kind of what it is. If you decide what gets jealous of what, the player then can infer a lot of different types of relationships of that,” says Pearson. “And we don’t have to label all of them. We don’t have to provide specific definitions and restrictions. We sort of just have to open up space, which is a really interesting design challenge . . . we say, ‘What’s the lowest common denominator that would unlock a lot of these things?’”

Building forgivable failure (like, why Sims still pee themselves)

You cannot win The Sims 4. But you cannot lose either. The way that the franchise has handled the topic of failure has evolved over time, climbing Maslov’s hierarchy of needs to be less about survival than everything else in life.

“When you go back and play The Sims 1, it is very hard to keep your Sims alive. They caught fire all the time. It was a very dangerous world in The Sims 1, the plate spinning was really hard,” says Pearson. “So, when we moved into The Sims 2, we wanted to introduce a different level of pushback, a little bit higher up the sort of chain of needs.” Sims began failing at the meta layers of life, like being too lonely.

But by The Sims 3 and 4, everything got a little bit easier about life. “Your Sims don’t fail so much as they just aren’t thriving, and that you can do so much more when you’re working with them, nurturing them, and pushing them along the way,” says Pearson.

Micromanaging has been tuned down in interest of choose-your-own-adventure story charting. If you aren’t spending every moment feeding yourself so you don’t starve, or showering so you don’t stink, you can spend more time, say, turning an entire town into vampires.

But notably, you still need to tend to your Sim. You even need to make sure that they use the bathroom now and again, or else, yes, after 25 years, they will still pee themselves. This micromanagement isn’t just gamification to keep the player active, but core to the emotional draw of The Sims.

“There’s a certain amount of pushback that the game still needs for you to believe that these are little people that need you, and that could be a mode of failure, like having an accident or starving. We try to make those entertaining as well: things like being hit by a meteor because you were stargazing for too long,” says Pearson. “Because at the end of the day, that is a reminder that there is a little bit of humanity in them that you need to pay attention to, and that you can’t just treat them like some ants and it’s fine if they die. You want to care about them.“

And perhaps that’s the real appeal of The Sims after two and a half decades. In a world where we constantly dehumanize one another, reflexively hating people as avatars on social media, The Sims offers another way—where even a few polygons and lines of code can be worthy of our care.