The hundreds of billions of pounds of waste produced by America’s dairy cows every year has long been a headache for farmers.

Manure is expensive to manage and, to state the obvious, it smells terrible, which can lead to complaints, protests, and lawsuits from neighbors — even the occasional fine or misdemeanor charge. And when dairies store their manure in giant open-air lagoons, the most common and cheapest method, it becomes a climate problem: As the manure decomposes, it produces methane, a climate “super pollutant” that accelerates climate change at a much faster rate than carbon dioxide.

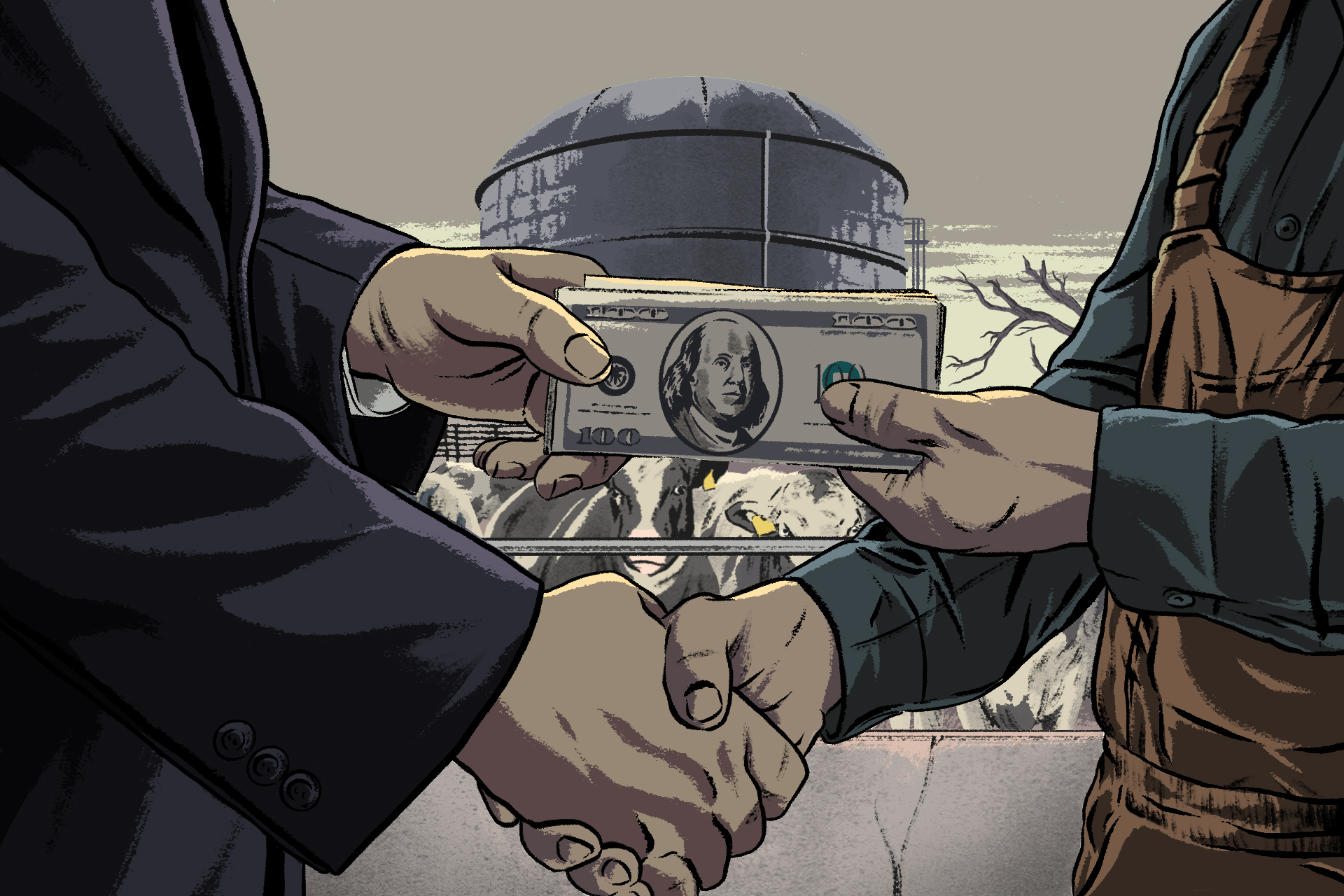

But in recent years, a growing number of large dairy operations have managed to simultaneously turn their costly, burdensome manure into money, and their climate problem into a supposed climate solution.

This is the third in a series of stories on how factory farming has shaped, and continues to impact, the US Midwest. You can visit Vox’s Future Perfect section for future installments and more coverage of Big Ag. The stories in this series are supported by Animal Charity Evaluators, which received a grant from Builders Initiative.

This alchemy relies on a machine called a biodigester, which usually comes in the form of a massive tank that holds manure, or as a seal that covers the lagoons where dairy farms store manure. As bacteria breaks down the manure and generates methane, biodigesters trap it — and other gases — to produce what’s known as “biogas.” Like fossil fuel-derived natural gas, biogas can be used to fuel cars and trucks, generate electricity, or heat homes and businesses.

The narrative that these simple machines can get rid of methane and turn manure into a climate solution, all while providing farmers a new revenue stream through the sale of the gas, has proven compelling across the political and corporate spectrum. A broad coalition of livestock groups, fossil fuel giants, agriculture and environment regulators, utility companies, Republicans and Democrats, and a handful of environmental groups has coalesced to hail manure biogas as a win-win, untapped source of renewable energy.

Cutting methane emissions, which account for 12 percent of US climate emissions, is a crucial component of the country’s efforts to slow down global warming. The Biden administration has designated manure biodigesters as a key part of its agricultural methane strategy.

To harness biogas’s potential, a sprawling web of generous federal and state grants, tax credits, technical assistance programs, and loan guarantees have been developed to build out biodigester infrastructure. There’s also a federal program, along with numerous state programs and private markets, that issue valuable credits to dairy producers and energy companies for biogas.

But while manure biodigesters do provide some benefit by trapping methane that would otherwise end up in the atmosphere — and reducing farm odor — to many in the environmental community, they represent an insidious form of greenwashing. A coalition of environmental, public health, and agriculture groups, with backing from some members of Congress, has formed to push back against the rise of biogas — what they have renamed “factory farm gas” — arguing that its win-win narrative is too good to be true.

Biodigester critics say that, at best, the process is a costly and inefficient use of America’s precious climate funding.

They often point to analyses by University of California, Berkeley agricultural economist Aaron Smith, who in 2023 estimated that it costs $1,130 per cow per year to build and operate a biodigester that generates just $128 worth of gas per cow.

“These things are really expensive — the cost of constructing and operating biodigesters is 10 times the value of the gas that it produces, and so it’s a very inefficient way to produce gas,” Smith told me. “There’s no way that you would ever justify that on economic grounds, so the only way to justify it is if it’s really valuable to society to reduce those methane emissions, and stop them from escaping.”

Stopping that methane is valuable to society, but with manure biodigesters, the costs may outweigh the benefits.

In a new report, anti-factory farming nonprofit Farm Forward found that the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), President Joe Biden’s landmark climate legislation, funneled over $150 million in subsidies to manure biogas projects in 2023 alone, primarily through grants under the US Department of Agriculture’s Rural Energy for America Program (REAP) and valuable tax breaks.

Hundreds of millions of additional IRA dollars could be dished out to manure biogas projects over the next few years, according to Farm Forward. After the passage of the IRA, the American Biogas Council welcomed its potential to “fuel growth of the biogas and clean energy industries for years to come.” Hundreds of millions of dollars have also been granted by California, which has the most extensive biogas program in the US.

At worst, critics say, manure biogas further enriches, entrenches, and expands a brutal factory farm system by incentivizing dairy farms to grow herd sizes in order to produce more manure and thus receive more lucrative federal and state credits from the gas that these “cash cows” generate. That’s at odds with the consensus among climate scientists, who warn that rich countries like the US must drastically reduce livestock populations — particularly cattle — to meet global warming targets.

It has also created a new revenue stream for oil and gas giants, such as Chevron, BP, and Shell, who have invested in biogas projects and sell it under the guise of renewable energy.

Biogas may seem renewable on its face; so long as people consume dairy, cows will keep generating manure. But this marketing sleight of hand belies two fundamental aspects of US dairy production. The first is that cow manure on its own doesn’t naturally contain methane; rather, the way that large dairy operations store manure produces the potent greenhouse gas, despite low-methane alternative storage methods. Second, the US has long had an oversupply of milk; we could meet dairy demand with fewer methane-generating cows.

“Our sense is that the IRA is being perverted to entrench Big Oil and Big Ag — that the incentives of the IRA are doing real harm, both, I think, for the climate movement and certainly for efforts to reform and transform industrial animal farming towards more sustainable, humane forms of agriculture,” said Andrew deCoriolis, executive director of Farm Forward.

Over the next decade, greenhouse gas emissions are expected to decline in every sector except agriculture, where emissions are projected to slightly increase. Instead of incentivizing farmers to grow more climate-friendly foods or finally regulating farm pollution, as some other countries have begun to do, US policymakers — using funds from the IRA and elsewhere — have doubled down on throwing money at technologies like manure biodigesters. They provide some modest albeit expensive short-term environmental benefits, but at the cost of further locking us into the animal factory farming model.

“It’s this perpetual mill of handouts,” said Tyler Lobdell, staff attorney with the nonprofit Food & Water Watch, “and all of these decisions we’re making today are going to make it so much harder to stop that gravy train down the road.”

How California sparked a “brown rush”

America’s first biodigester was installed on a Minnesota pig farm in 1976, and it remained a niche technology for decades. But everything changed around 2018, which marked the start of the biogas “brown rush,” as it’s sometimes called. That year, biogas became incredibly valuable thanks to California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS), a program that requires gasoline and diesel companies that operate in the state to lower the carbon intensity of their transportation fuels.

Here’s how the program works: California sets a target to reduce the average carbon intensity for transportation fuels used in the state, and because gasoline and diesel are so carbon-intensive, the companies that import and sell them rack up carbon deficits. If you are a company making an alternative fuel with a lower carbon score compared to conventional gas and diesel — like a solar power producer, or a dairy farm with a biodigester — you can earn credits and sell them for a profit to the fuel companies that need to reduce their carbon intensity under California’s law. Some of the cost is passed onto consumers at the pump.

Each type of fuel is assigned its own carbon intensity score, and the lower the score, the more credits a company can earn from producing that fuel. Before 2018, manure biogas’s value was relatively low in the LCFS program, so few dairies participated because it wasn’t worth the cost of installing and operating a biodigester. But then California updated how it calculates manure biogas’s carbon intensity by considering it a source of “avoided methane” — methane that otherwise would’ve escaped into the atmosphere and warmed the planet.

While it’s technically true that manure biodigesters are diverting methane from the atmosphere into gas tanks, considering it a form of avoided methane rests on a faulty premise. That’s because cow manure doesn’t inherently contain methane. Rather, most large dairies store manure in lagoons — the cheapest form of manure management — which produces methane. Dairies with biodigesters aren’t sucking greenhouse gases out of the air, like carbon dioxide removal projects; they’re generating new methane they didn’t need to generate in the first place and then trapping it.

But California’s decision to count manure biogas as avoided methane made it far and away the most valuable alternative fuel in the program, with an average carbon intensity score of around -300 — much lower than even electricity derived from solar or wind power, which has a carbon intensity score of zero. Diesel is around 100.

“That policy decision is what opened the manure gold rush floodgates,” Lobdell said.

From 2020 to 2024, the number of manure biodigesters nationwide nearly doubled from 175 to 343. While most biodigesters have been built in California because it’s the top dairy-producing state, the credits can be earned by farmers and energy companies in any state and sold to fuel companies operating in California, with many built in dairy-rich Texas and across the Midwest.

According to some energy wonks, this unleashing of manure biogas has come at the expense of faster vehicle electrification. Biogas accounts for less than 1 percent of energy used in California’s transportation fuels, but has earned 20 percent of LCFS credits, requiring significant amounts of capital that might have otherwise gone toward electrification projects, such as EV charging stations.

Jim Duffy, who formerly managed the LCFS program at the California Air Resources Board (CARB), has lambasted the dairy sector’s preferential treatment: “No other industry is treated as if their methane pollution is naturally part of the baseline and then lavished with large financial incentives for simply reducing their own pollution.” For example, similar to dairy manure lagoons, garbage landfills generate methane, but capturing that methane isn’t considered a form of “avoided methane” and is valued at a fraction of manure biogas.

Last month, a group of environmental justice organizations, including Food & Water Watch, sued CARB, arguing it had failed to analyze the impact that incentivizing manure biogas, and the resulting expansion of dairy farms that benefit from the credits, would have on the environment and public health of nearby communities.

This concern — that by making manure so valuable California is incentivizing big dairy farms to get even bigger — is at the heart of anti-factory farming advocates’ critique of manure biogas. “In the Central Valley, we live near 90 percent of cows in California and some of the largest dairy operations in the entire world,” María Arévalo of Defensores del Valle Central para el Aire y Agua Limpio, a plaintiff in the lawsuit, wrote in a press release. “We raise time and time again that the conditions and impacts in our communities are getting worse as dairies are getting bigger and dairy digesters are installed.”

Some small-scale analyses bear this out. According to an analysis by Friends of the Earth and the Socially Responsible Agriculture Project, dairy farms with biodigesters in Kewaunee County, Wisconsin, increased their herd sizes to generate more profit — more cows, more manure, more valuable carbon credits (Disclosure: Last year, my partner worked with Friends of the Earth on a short-term consulting project unrelated to biogas.)

Based on an analysis from Iowa newspaper The Gazette, the same has occurred in Iowa, and Inside Climate News found that over 20 California dairies in various stages of biodigester development have sought approval to increase herd size.

According to Smith, California’s total dairy cow population didn’t increase in the years after the 2018 decision. However, the state’s herd sizes had been declining for years; the dairy biodigester boom may have just helped stave off further decline.

It’s worth noting that dairy cow manure accounts for just 4.4 percent of US methane emissions. Another 6.4 percent come from dairy cows’ burps, which biodigesters do not trap. (The rest of US methane primarily stems from beef cattle, fossil fuels, and landfills.) So if some dairy producers are growing their herd sizes to generate more biogas, they could inadvertently be worsening the problem by increasing methane emissions from cow burps.

Patrick Serfass, executive director of the trade group American Biogas Council, dismissed the argument that biodigesters incentivize farms to get bigger: “I don’t think anyone’s shown causation,” he told me. “I think there might be some correlation.”

It’s also possible that some farms get bigger due to biogas incentives and cause smaller operations, which can’t compete with them on price, to shutter. If that’s the case, it would exacerbate a long-running trend of consolidation in the dairy sector — one that the Biden administration has otherwise sought to stop. Further consolidation would also mean more concentrated pollution in rural communities, pitting both California’s and the Biden administration’s methane goals against their environmental justice initiatives.

CARB declined an interview request for this story and declined to comment on the pending lawsuit. Over email, a spokesperson said that the LCFS is “a successful policy tool among California’s portfolio of innovative measures to address climate pollution and improve air.”

Read more Vox coverage of how factory farming built America

How public universities hooked America on meat

Big Milk has taken over American schools

American government built the meat industry. Now can it build a better food system?

How the most powerful environmental groups help greenwash Big Meat’s climate impact

At the end of 2021, one cow could earn about $2,600 per year on average in combined credits from California’s program and a federal program, a form of double dipping common in manure biogas projects, while one cow’s milk was worth about $4,500 per year. That was the industry average — but some farmers said their manure was about as valuable, or even more valuable, than their milk — a fact that could have encouraged some to grow their herds.

Over the last few years, however, the value of California’s carbon credits has crashed due to manure biogas and other alternative fuels flooding the market. Today, due to falling LCFS credit value, biogas credits from one cow are worth closer to $1,600 annually.

But this past November, California increased the carbon reduction requirement for transportation fuel providers, a decision expected to both raise the value of the program’s credits and make conventional fuel providers more reliant on alternative fuels like manure biogas.

Meanwhile, some dairy researchers believe the industry’s future lies in the Upper Midwest and Great Lakes regions, partly as a result of climate change — the region has a temperate climate and abundant freshwater, unlike drought-prone California. Midwest states are also actively luring California dairy farmers to their region with promises of fewer regulations.

The region could be key to the future of the biogas industry as well. In recent years, dozens of new manure biodigesters have been built in the Midwest, and numerous state legislatures there have introduced pro-biogas bills.

“They want a new market,” said Trevor McCarty, a policy fellow at Farm Forward. The brown rush appears to be slowly moving eastward.

The brown rush moves eastward

Over the last few years, according to another new report by Farm Forward, the pro-biogas coalition of policymakers, regulators, fossil fuel giants, and agribusiness have been busy building that new market. The Midwest, with its ample dairy and pig populations and ag-friendly state legislatures, is primed to highly value biogas like California and impose few regulations on the industry.

In 2021, Iowa passed a bill that lifts the cap on the number of animals a farm can house if it has a biodigester, which directly led to increased herd sizes. In 2023, the EPA co-hosted a conference in the state — sponsored in part by Chevron — to “boost curiosity about anaerobic digestion’s potential in the region.”

An analysis by Investigate Midwest found that in 2022 and 2023, far more federal rural clean energy funding in Wisconsin went toward biogas projects than installing solar panels on farms or making energy efficiency upgrades, bucking the program’s national spending ratios, in which most spending goes to solar projects.

Now, the energy and agriculture industries are pushing for a slate of pro-biogas bills in Michigan, paving the way for an expanded manure biogas sector in the state, according to Farm Forward.

“It’s a sort of two-prong approach,” McCarty told me. On one end, the two industries are lobbying for a Michigan Senate bill that would set up a transportation fuel program similar to California’s, which McCarty said will be “very lucrative for [industry’s] own interests.” On the other end, the Michigan Farm Bureau, an agriculture lobby group, supports a pair of bills in the state’s House that would exempt digestate — the solid manure that’s left over from biogas production, which poses water pollution risks — from key regulations.

None of the bills passed in Michigan’s most recent legislative session, which just ended. The new session begins in a few days.

“It’ll be something that we’ll look to continue to iterate on and reintroduce again next year,” Jane McCurry, executive director of Clean Fuels Michigan — a trade group that advocates for alternative transportation fuels — said about the bill to set up a Michigan transportation fuel program.

Many Michigan environmental groups don’t want manure biogas in the program. Asked if Clean Fuels Michigan would consider advocating for cutting it, McCurry said, “We’re really committed to continuing to iterate on this policy. … We’re very much open to continuing to find that middle ground and compromise.”

Cheryl Ruble, a physician and volunteer advocate with Michiganders for a Just Food System, which has lobbied against the bills, said the fight over biogas in the proposed clean fuel standard has been difficult.

“The industry has done a very, very good job on the marketing end,” Ruble told me. “We’re fighting an excellent and well-financed, well-funded marketing campaign. We’re also fighting a lot of deep pockets: Big Energy, Big Ag, Big Waste, Big Utility, Big Finance.” The seemingly win-win narrative of manure biogas has been appealing to both political parties: Democrats introduced the clean fuel standard bill, while a bipartisan group of lawmakers introduced the deregulatory bills.

A number of other states are also considering similar programs, including leading dairy states New York and Minnesota. Earlier this year, New Mexico — another top dairy state — passed legislation to build such a program, but it’s not yet decided how it will value manure biogas.

Despite the Michigan bills failing to move this legislative session, some biogas projects have managed to find resources in Michigan’s state coffers. In October, the state-run Michigan Strategic Fund awarded Chevron and biogas developer BerQ RNG tax-exempt bonds, valued at $100 million and $235 million, respectively, to finance manure biogas projects under the banner of supporting “small businesses.” Wisconsin, Iowa, and other states have issued similar tax-exempt bonds, which deprive the states of millions of dollars in tax revenue.

On top of state-level programs, there are some two dozen federal programs across the Departments of Agriculture, Energy, Treasury, and Environmental Protection available to farmers and energy companies to build biodigesters. The Treasury Department is also weighing whether electricity producers that use manure biogas can receive clean energy tax credits. But increased scrutiny over manure biodigesters, and the potential for the incoming Trump administration to rein in climate spending, has put some of the optimism about biogas into question.

Better than biogas

Despite the shortcomings of California’s decision to value manure biogas so highly, there was some logic — however flawed — to the decision. In 2015, California passed a law to significantly reduce methane emissions by 2030, and a lot of the state’s emissions come from livestock due to its big dairy industry. There was already some biodigester infrastructure built in the state, so building out more was an immediately viable option that already had buy-in from the industry.

According to the state, by 2019 California’s dairy biodigester program was cutting one-quarter of its dairy methane emissions each year, the equivalent of taking nearly half a million cars off the road.

But “if we would completely shake the Etch-A-Sketch and start over, I wouldn’t prioritize anaerobic digesters on dairy farms as being where I would want to invest a lot of money,” Smith said. “I would want to have a lot of research and development into better and more efficient ways to handle manure so as to reduce methane emissions.”

According to an analysis by the Breakthrough Institute, an environmental think tank, federal R&D funding to reduce emissions from livestock manure received $4 million a year from 2017 to 2021 — that’s only 3 percent of total agricultural climate mitigation R&D funding despite manure accounting for 13 percent of agricultural emissions.

Serfass, from the American Biogas Council, said that given America’s need to reduce methane as quickly as possible, biodigesters are worth it: “I would submit that there’s a very sound scientific argument that spending money near-term on reducing methane emissions in the near term has a very, very high value, therefore it might be worth paying a little bit more” on a known solution like biodigesters.

Lobdell, with Food & Water Watch, doesn’t dispute the urgency of America’s methane problem, but argues that incentivizing manure biogas lacks foresight: “The last thing we should do is rush into short-term supposed solutions that are very predictably locking in long-term, durable problems. That’s bad policy.”

One set of possibilities for curbing livestock emissions include feed additives, such as Bovaer — a product that when fed to dairy cows daily can reduce methane from their burps by around 30 percent — which are much more cost-effective in reducing methane than manure biodigesters. It shows promise, but questions remain about who will pay for it and whether it could also create perverse incentives like biogas.

The government could also simply pay dairy farmers to raise fewer cows, which some environmental groups say would be cheaper than funding biodigesters and offer the surest way to reduce both climate and localized pollution. Dairy prices and demand are already somewhat artificial; by one estimate, 45 percent of dairy production is subsidized by the US government. The Netherlands has begun paying farmers to stop raising pigs and other livestock to reduce the nation’s nitrogen pollution.

Alternatively, Denmark is funding a slate of policies to incentivize farmers to grow more plant-based foods, which have much smaller environmental footprints when compared to animal-based foods. The country will also modestly tax livestock emissions starting in 2030.

The simplest solution would be to make the dairy industry reduce its methane however it sees fit, at its own expense, rather than rely on increasing infusions of taxpayer dollars to solve a problem of its own making. Manure management systems in which the manure is stacked in outdoor mounds and exposed to oxygen — as opposed to the poop lagoon systems used by most commercial dairies — largely avoid releasing methane.

“There are dairies right now who do not have this manure methane problem,” Lobdell said about farms that use these “dry” management systems.

Despite all the good arguments against biogas, for the industry, there’s no limit to its growth potential. By the American Biogas Council’s count, there are currently 53 manure biogas operations in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Iowa, but there’s potential for another 1,900 or so, and an additional tens of thousands across the country. One major biogas company said it plans to spread “like an amoeba.”

“The whole roadmap here is never to just pollute less,” Lobdell said. “The long-term road map here is digesters at every mega dairy, producing as much methane as possible for use in other sectors.”