You tumble into Cecchi’s from 13th Street. Before you’re even in the door of the restaurant in New York, you’re peering through gauzy half-curtains, as if backstage, about to face the clientele-cum-audience. Inside, a mural echoes your voyage, depicting the lurch off the subway through sweaty depths, the hasty flight toward conditioned air, the host bending over backward to find you a seat. Vampish oil-painted figures parade from the restaurant’s entryway to its depths through toothsome scenes. In the kitchen, a painted chef offers an oyster to a busty brunette. The dining room features a painted circus of limbs and pointed shoes. In the washroom, a couple does each other’s makeup, pouting at a third face that hovers winkingly in the mirror. Black velvet curtains frame a door at the restaurant’s far end, teasing silhouettes of high-heeled nudes that dance table-height along the walls.

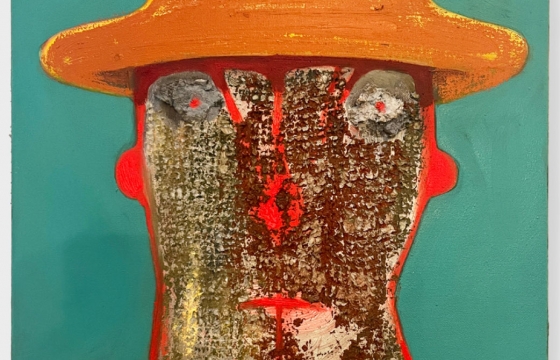

Commissioned by maître d’hôtel and Off-Broadway actor turned restaurateur Michael Cecchi-Azzalino for his new haunt on the site of the defunct literary hub Café Loup, artist Jean-Pierre Villafañe’s (b. 1992, Puerto Rico) trio of allegorical murals Into the Night (2023) depicts the seven deadly sins in portraits of cosmopolitan vice. Playing seamlessly into the art deco fixtures that theatrically light the restaurant’s interior, Villafañe’s figures are caryatid statuesque, with sharply sculpted geometries evoking a Bauhaus grotesquery. New York as urban jungle or late-night denizen is Villafañe’s subject, and he renders it as a study in restraint and Dionysian release.

In Villafañe’s universe, as in our own, buildings dictate the flux and flow of life. Place becomes a character in tableaux that borrow perspectival tricks as easily from city streets as from Fra Angelico. This emphasis on architecture is honed by years of study, first at the Savannah College of Art and Design and then at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation. Growing up in Puerto Rico, his painterly work intersected with the built environment in graffiti throw-ups both condoned and covert, covering apartments, plazas, and abandoned warehouses. In a studio visit, the artist told me he sees traces of his improvisatory street art in the sketches that are the basis for his paintings. His sinuous limbs and rectilinear tendencies threaten to blur bodies with the architectural features that surround them. Tits and ass become spherical studies. Fishnets echo masonry. Contoured cheekbones and arched brows take on the sinewy, structural quality of a buttress.

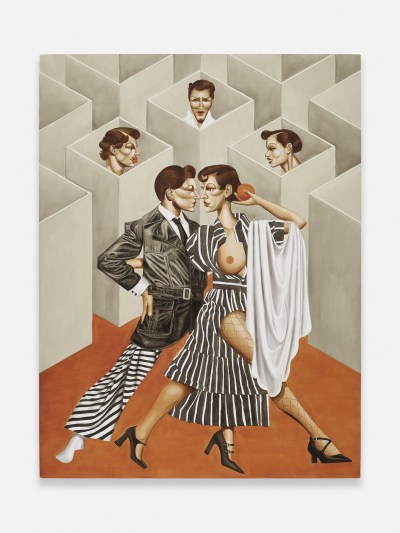

Figures push at and collapse the spaces that contain them in Villafañe’s hedonic portraits of city life. Recently, the artist has taken to observing the city with a god’s-eye view, with a studio on the 28th floor of 4 World Trade Center, where he is an artist-in-residence at Silver Art Projects. In paintings black, white, and burnt sienna all over, Villafañe’s characters rebel against Puritanical efficiency and its “compartmentalized timetables of desire,” to borrow his words. They play hooky on the rooftop (Offsite, 2024). They quiet quit, slinking off to orgiastic liaisons behind closed office doors (Playtime, 2024).

In the artist’s summer 2024 exhibition “Playtime” at Charles Moffett, New York, the striped pajama-pant aesthetic of post-pandemic office wear is willfully confused with the striation of cell bars, figures doubly entrapped in “coffin cubicles.” The artist is sympathetic to the Severance-style repression implicit in the day-to-night of the bureaucratic worker and desiring self, stashing joys for the afterhours when, in Villafañe’s words, “you’re released into the wilderness again to become a rascal.” In his riotously duplicitous paintings, cabaret chorus lines converge with phalanxes of commuting automatons, masses of bodies that become sites of both work and play.