The wildfires in Los Angeles have destroyed entire neighborhoods, ravaging more than 16,000 homes and structures in Altadena and Pasadena, alone.

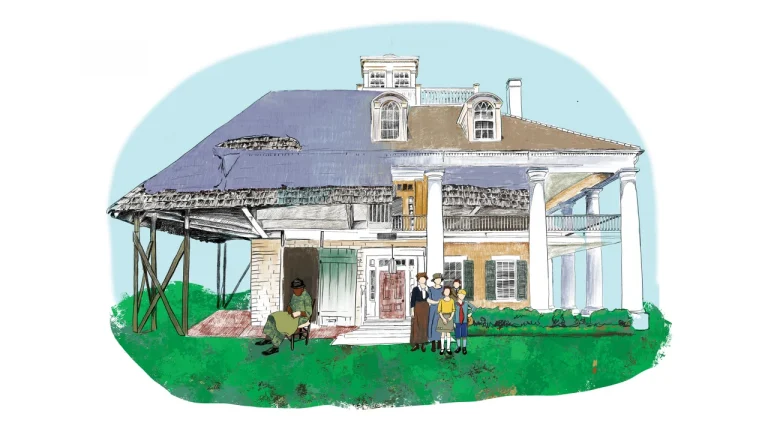

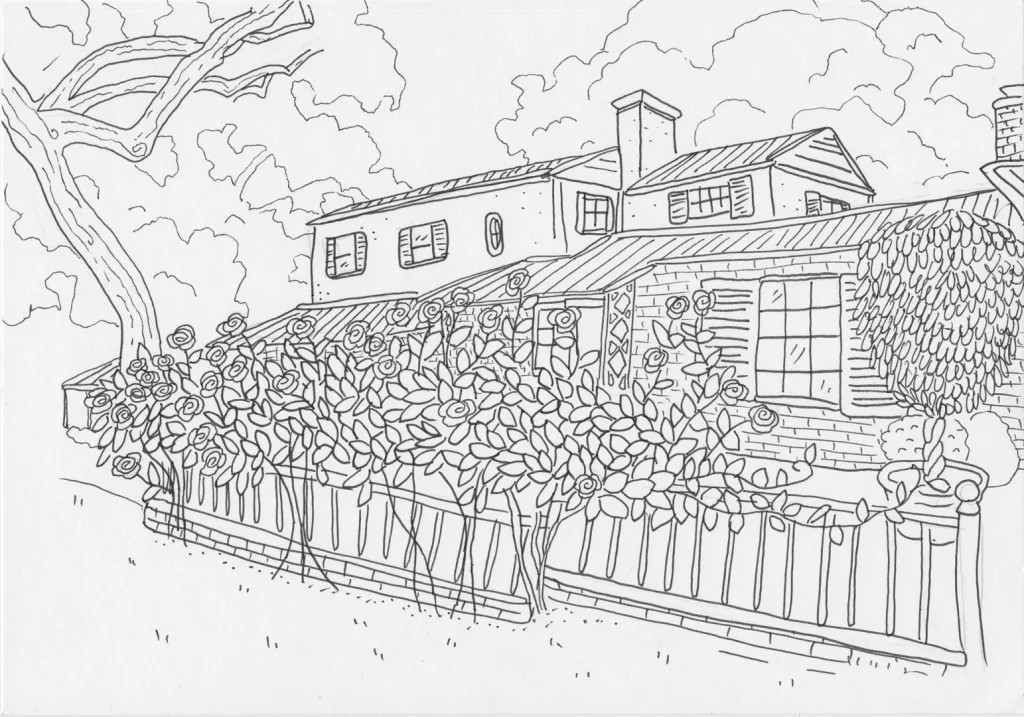

Asher Bingham, an L.A.-based portrait artist, spends her days taking in the extent of what has been lost. She spends hours at her drawing table, illustrating homes that have been lost and then mailing them to the people who used to live there. One day, she hopes to have an art show that features different neighborhoods, with pictures of homes along with the stories of the people who lived there.

Two days after the fires began, Bingham took to Instagram, inviting people who had lost their home to send in a request, and she would draw their home for free. She was’t expecting a big response—perhaps a few dozen people. But the post went viral. She’s already received more than a thousand requests.

Bingham came up with the idea for the project because a close friend of hers was profoundly impacted by the Eaton Fire. This friend was getting married in Las Vegas and when the fires broke out, she enlisted Bingham to go over to her house to save her cats. The fire eventually burned down the house. “It was both the best and worst day of her life,” she recalls. “She got married at the same time as she lost her home.”

Bingham didn’t know what to do to comfort her friend. But as an artist, she figured she could draw the home and give it to her. “I had just been to her house, and I could remember all the details,” she says. She gave it to her friend and didn’t hear back for several days. “I was worried I had perhaps done the wrong thing,” she recalls. But eventually her friend said she was so deeply moved by this gesture of kindness and a piece of art that would allow her to remember her beloved home.

The Instagram post followed. And suddenly, thousands of people were asking for similar pictures of their home. It takes Bingham between 30 and 90 minutes to do an illustration of a home, depending on how complex it is. She now works 12 hours a day on these pictures.

The fact that these pictures are hand drawn is important, Bingham says. With AI technology, it’s possible to create digital illustrations of these homes. But she says that the time and labor that goes into these drawings is the whole point. “These people have gone through an unbelievable loss,” she says. “This is not just a representation of their house, but a small gesture of kindness from a stranger.”

She quickly realized there’s no way she would be able to get through the entire list in a timely manner. So, she’s reached out to other artists around the country, asking if they were willing to contribute to this work. More than a hundred responded. Bingham selected a handful that shared her aesthetic approach, and they now work collaboratively to go through the pile.

Now, they have a spreadsheet where they track each person who has made a request for an illustration. Those sending in requests send in photos of their house, and sometimes stories, which Bingham saves in the spreadsheet. They then go through the list, illustrating each house before creating a high resolution scan of the picture and mailing the illustration to the homeowner. Bingham’s friend has volunteered to pay for the shipping fees. “It’s six dollars per picture, which isn’t much, but it adds up when you’re sending over a thousand,” she says.

Eventually, Bingham would like to show all of the pictures together in an art exhibit. It would be a way for people to explore the neighborhoods that have been lost forever, and get a sense of the charm and uniqueness of the various homes. She can already imagine captions next to each picture, with stories from the people who lived there. But for now, she’s spending her days at her drawing table, trying to capture each tiny detail of people’s home with as much care as possible.