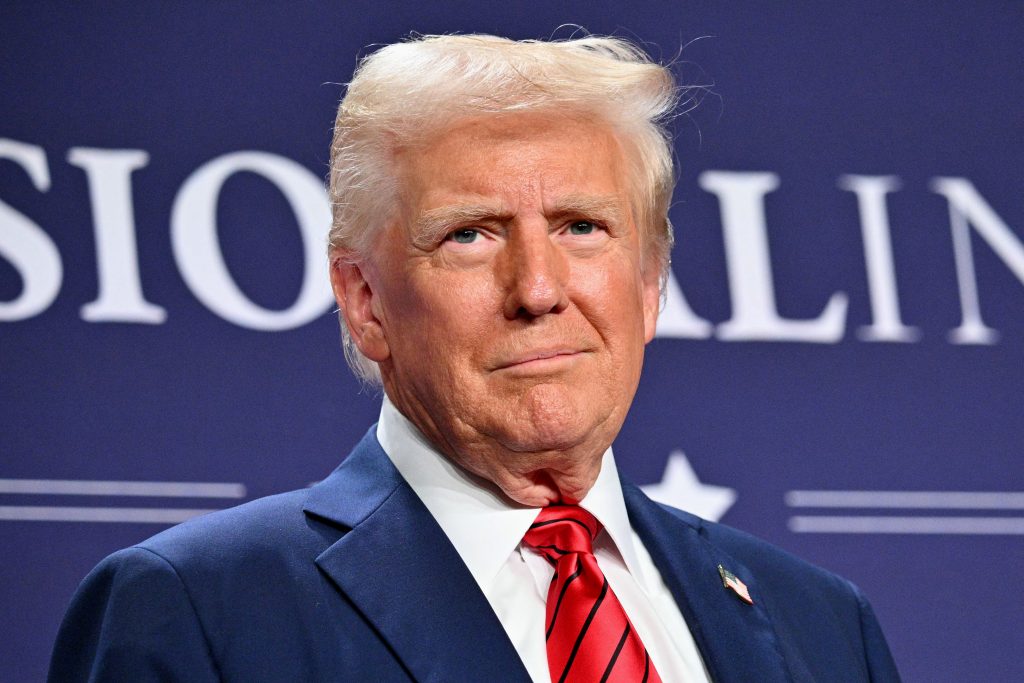

President Donald Trump recently attempted to fire Gwynne Wilcox, a member of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and its former chair. This attempted termination is just one of many similar actions Trump has taken, but it is also a singularly important move by Trump because it could trigger a legal fight that could significantly expand the powers of the presidency.

Most federal agency leaders and similar officials can be fired at will by the president. But federal law provides that members of the NLRB, like top officials at a number of similar agencies, may be removed “for neglect of duty or malfeasance in office, but for no other cause.” So, unless Trump has evidence that Wilcox ignored her duties or engaged in misconduct, this law forbids him from removing her until her term in office expires.

However, much of the federal judiciary — including all of the Supreme Court’s six Republicans — subscribes to a legal theory known as the “unitary executive,” which raises serious doubts about whether Congress can give this kind of job security to an official like Wilcox. In its strongest form, the unitary executive gives the president control over every federal government job that isn’t part of Congress or the judiciary — meaning he can hire and fire at will — although it is unclear whether any of the justices would take this theory that far.

If Wilcox decides to challenge Trump’s decision to fire her, that is likely to trigger one of the most consequential legal fights of Trump’s two terms in office. Even if she doesn’t, Trump’s administration appears ready to fire so many federal officials that a legal showdown over the unitary executive is almost certainly inevitable. If Trump prevails in that contest, he would not simply gain the power to decide how labor law is enforced, he will also gain unprecedented power over agencies like the Federal Reserve that have the power to reshape (or ruin) the US economy.

These firing disputes, in other words, could be one of the most significant milestones toward converting Trump from a public servant into a king.

So what, exactly, is the unitary executive?

The idea of a unitary executive begins with a seemingly innocuous passage of the Constitution, which states that “the executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” As proponents of the unitary executive point out, and as Justice Antonin Scalia put it in a famous dissenting opinion, this provision “does not mean some of the executive power, but all of the executive power” is held by the president.

One thing the Constitution isn’t very clear on, however, is what the “executive power” is.

Some of the answer to this question can be found in Morrison v. Olson (1988), the case where Scalia wrote his consequential dissent. Morrison upheld a 1978 law, which expired in 1999, that allowed a panel of judges to appoint an “independent counsel” with the authority to investigate and prosecute high-ranking government officials.

Significantly, this independent counsel was not fully controlled either by the president or by any of the president’s subordinates, and could only be removed by the attorney general “for good cause, physical disability, mental incapacity, or any other condition that substantially impairs the performance of such independent counsel’s duties.”

The Court upheld the statute in a 7-1, leaving Scalia alone in dissent to write what became one of the foundational texts of the unitary executive theory.

Scalia argued that “governmental investigation and prosecution of crimes is a quintessentially executive function,” and thus this power could not be insulated from the president. Because, in Scalia’s view, all executive functions must be vested in the president, no federal prosecutor could exist who couldn’t be fired either by the president himself, or by some official like the attorney general who is responsible to the president.

How Scalia’s opinion gave Trump the power to order malicious prosecutions of his enemies

Scalia’s claim that “investigation and prosecution of crimes is a quintessentially executive function” is quoted prominently in Trump v. United States (2024), the Republican justices’ decision that Donald Trump has broad immunity from prosecution for crimes he commits using his official presidential powers. It features heavily at the beginning of the section enabling Trump to order the Justice Department to target his political rivals.

According to the Republican justices in Trump, because “prosecutorial decisionmaking is ‘the special province of the Executive Branch,’” and because “the Constitution vests the entirety of the executive power in the President,” it follows that Congress cannot pass a criminal law that limits the president’s authority to order prosecutors to target particular individuals or to open particular investigations.

Thus the theory of the unitary executive grew from a rule governing who could be fired by whom, into a rule that allowed a sitting president to order a campaign of malicious investigations and prosecutions against a political rival.

It’s worth noting that Scalia’s claim that prosecution is a “quintessentially executive function” stands on weak historical ground. As law professor Jed Shugerman wrote in a 2019 essay, early Americans — including many of the people who drafted the Constitution — had a much more nuanced view about who could wield prosecutorial authority.

Shugerman claims that prosecutions led by private attorneys were the norm “through the mid-nineteenth century.” And some states, including Pennsylvania and New Hampshire, still maintain vestiges of this old system.

Similarly, Shugerman notes that “federal judges themselves led what appeared to be prosecutions during the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794.” Current law still sometimes gives federal district judges the power to appoint interim US attorneys who oversee nearly all federal prosecutions in a given geographic area in certain cases.

So Scalia’s idea that prosecution is exclusive to the executive is a fairly new idea. Nevertheless, it enjoys such strong support from the Supreme Court’s Republican majority that this notion could shape the law for many years to come.

Why is Wilcox’s firing so significant?

One uncertain question is whether this Court, despite its general support for the unitary executive theory, will extend that theory to agencies like the NLRB, which are run by multimember boards rather than by a single leader like most federal agencies.

In Humphrey’s Executor v. United States (1935), the Supreme Court upheld a law that protected the five commissioners of the Federal Trade Commission from being fired except for “inefficiency, neglect of duty, or malfeasance in office.” Much of the Court’s decision is rooted in a claim that the FTC’s “duties are neither political nor executive, but predominantly quasi-judicial and quasi-legislative.” The Court also pointed to the fact that the FTC’s design was supposed to ensure that its members would “act with entire impartiality,” and to ensure that they “exercise the trained judgment of a body of experts.”

This rule establishing that multi-member agencies are less subject to presidential control than an agency with a single director is hard to square with the Court’s more recent decisions endorsing a unitary executive. Yet those recent decisions have largely danced around the question of what to do about Humphrey’s Executor — often criticizing that decision, but not yet overruling it.

It’s likely that some of this hesitation stems from the important role played by one federal agency with a multimember board: the Federal Reserve.

The Federal Reserve is supposed to strike a delicate balance between maximizing job growth and controlling inflation. One danger, if the Fed is not free to act independently of the president, is that the president might pressure the Fed to lower interest rates in order to temporarily stimulate the economy, even though this stimulus will bring inflation that will eventually cause more harm than if the Fed had done nothing.

This is not a hypothetical concern. In 1971, President Richard Nixon pressured Fed chair Arthur Burns to lower interest rates in advance of Nixon’s reelection race. Burns complied. The economy boomed in 1972. And Nixon won reelection by a historic landslide. But Burns’s action is often blamed for years of “stagflation” — slow economic growth combined with high inflation — in the 1970s.

To help prevent something like this from happening again, members of the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors enjoy similar legal protections to members of the NLRB and cannot be fired simply because the president wants to fire them. Should Humphrey’s Executor be overruled, however, that would mean that the unitary executive applies to Fed board members, and Trump (or any future president) would effectively gain the power to demand that interest rates be lowered.

Is there anyone Trump can’t fire under the unitary executive theory?

Taken to its logical extreme, the unitary executive theory suggests that Trump can fire literally anyone he wants to fire within any federal agency, regardless of whether that person is a civil servant whose job is protected by law. It is unlikely, however, that even this Supreme Court will say that Trump can strip civil service protections from all of the nearly 3 million civilian employees of the federal government. Scalia’s hallowed Morrison dissent, for starters, does not go that far. Instead, it suggests that total presidential control over federal employees is limited to “Officers of the United States.”

Though the Constitution describes the process by which these officers must be appointed, it does not clearly define who counts as an officer. The Supreme Court’s opinions on this topic, moreover, are rather vague — one opinion described an officer of the United States as someone who exercises “significant authority pursuant to the laws of the United States.”

As a practical matter, in other words, any civil servant fired by Trump or his subordinates will most likely have to litigate the question of whether they exercise “significant authority,” and thus count as an officer, if they want to get their job back. Non-officers are likely to retain their civil service protections, while officers are likely to be deemed to be subject to presidential control under the unitary executive.

That will place a heavy burden on any fired civil servant who wants to fight for their job, but it is also likely that, if any relatively low-ranking civil servants engage in this fight, they will ultimately prevail. Still, if all that Trump gains is the power to fire civil servants who exercise “significant authority,” that’s still a very big deal. Someone can do a lot to reshape an organization when they have total control over its senior-most employees.

It remains to be seen how the first stages of this fight will play out in court. If Wilcox — or any other terminated official in a similar role — decides to challenge their firing, that would give the justices a vehicle they could use to dramatically expand Trump’s power.