Aura Rosenberg explores the inner lives and desires of monuments from different epochs. The space between them is the space between us. Our private longings embed in an overarching universal history, in which ancient mythologies confront contemporaneity. Rosenberg questions this common domain: what does public space mean today? To whom does it belong? What is this scenario for its ostensible protagonists, namely statues and public sculptures?

Rosenberg’s solo show at the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź is titled after her series Statues Also Fall in Love (2018–24). This title combines two key references: art historian George L. Hersey’s book Falling in Love with Statues: Artificial Humans from Pygmalion to the Present and the 1953 filmic essay Statues Also Die by Chris Marker and Alain Resnais.

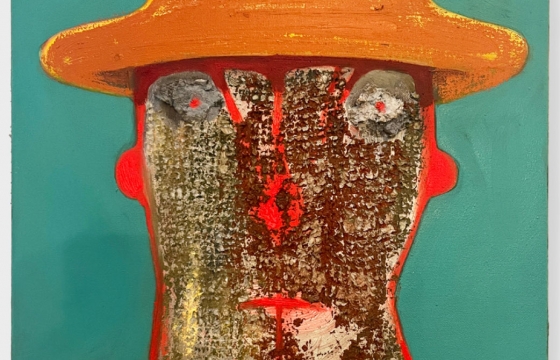

Rosenberg’s recent work centers on a series of lenticular prints that juxtapose contemporary images and classical iconography from Greek and Roman mythology. For “Statues Also Fall in Love” she produced black & white lenticular prints that flip back and forth seamlessly between photographs she shot of classical and neoclassical sculptures and sensual images in identical poses of present-day actors that she found online. With this approach the artist references the Apollonian and Dionysian opposition in ancient Greek culture. It brings our attention to the inconsistencies in interpretations of “pure white” archaeological artifacts, including canons of beauty, gender, nobility and eroticism. All depends on context. The museum sublimates otherwise sensual images, rendering them purely aesthetic. Accordingly, this series features iconic statues in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NY and the Alte National Galerie in Berlin, including Hercules and Aphrodite, Prometheus, Head of Hercules and Lucretia. The artist playfully reminds us, that monochrome marble statues, which we know from museums or sightseeing tours, originated as colorfully painted sculptures. The exhibition accordingly includes new colour prints depicting renaissance and mannerist masterpieces: The Rape of Polyxena, Fountain of the Ocean, David, Buontalenti Grotto and the well-known colossal Constantine Head and Hand at the Capitoline Museum

The installation Marbles (2018-24) offers a counterpoint to Statues Also Fall in Love. For this, Rosenberg began by gathering marble fragments from a quarry in Vermont. Next, she glued photographs of classical sculptures onto the rocks, collaging these images to match the contours of the marble. This created a trompe l’oeil effect which, in her words, “fooled you into thinking they were really ruins.”

In turn, the animation Angel of History (2013), inspired by Walter Benjamin’s famous allegory, presents a sweeping panorama of destruction. This five-minute video imagines the arc of history as a ruin culminating in the present, symbolized by a monumental scrap heap. In this narrative, a storm from Paradise, blows the Angel backward into the future. The angel sees animals, people, statues, buildings, heroes, and cities crash into a massive pile of rubble. Rosenberg’s animation visualizes the allegory in a vernacular that flirts with camp, kitsch, and computer games. For this, the artist culled images from online pictorial archives and shot her own photographs to depict the catastrophe of determinist progress. A flash of lightning at the end offers a glimpse of Paradise, where the film began—a hint of possible redemption. As Rosenberg put it: “the flash [ . . . ] interrupts the cataclysmic momentum and reminds the viewer of the dialectic of history in which the past can be recalled only in relation to the demands of the present.”

The Missing Souvenir (2003-24) consists of small replicas of Berlin’s Siegessäule / Victory Column (well-known from Wim Wender’s Wings of Desire). After noticing there were no souvenirs of this column, Rosenberg decided to produce an unlimited edition of them. The monument commemorates Germany’s 1870 victory over France in the Battle of Sedan, which ended the Franco-Prussian War and resulted in Germany becoming a nation state. In 1939 Adolf Hitler moved the column from its original location in front of the Reichstag to where it now stands in Tiergarten along an east-west axis through the city that he planned for the German army to pass on what he believed would be their victorious return from Russia. He also made it taller and broadened its base. Given this checkered history, perhaps the public has been hesitant to embrace the monument—hence no souvenirs. Ironically, inside it is a museum of other monuments.

Rosenberg has also made work about sculpture in her native New York City, namely the popular Charging Bull and Fearless Girl statues in the Financial District Arturo Di Modica created the bull in 1989 as a tribute to American enterprise. As a feminist retort, Kristen Visbal installed her Fearless Girl directly in front of the bull on International Women’sDay in 2017. Polemics aside, the psychological tension between the two works served as a starting point for another series of drawings and lenticular prints. Here, Charging Bull and Fearless Girl parallel the myth of the Minotaur and the labyrinth, recalling not only the famous classical iconography, but also the cult of Pablo Picasso. In 2019, due to Di Modica’s protests, city officials moved the girl away from the bull where she now faces the unresponsive facade of the New York Stock Exchange on Wall Street.

The Charging Bull and Fearless Girl statues are also the starting point for Rosenberg’s most recent film The Space Between Us (2024), made in collaboration with writer and filmmaker Veronica Gonzalez Peña. When the two figures faced one another, they stirred unconscious mythologies. Tourists and onlookers immersed themselves in the space between them, a space filled with seduction, the desire for innocence, and the allure of bestiality. This charged space promised to take its beholders on a dizzying, mythic journey. If the labyrinth is a model of the mind, then The Space Between Us moves us through its obscure sectors.

The exhibition does not omit another mythically “intersubjective” figure: the Unicorn, which appears from antiquity all over the world and in all civilisations, including the most discussed public sculpture and site of the Przesiadkowo in Łódź.

Curated by

Barbara Piwowarska

at Muzeum Sztuki, Łódź

until March 30, 2025