Whenever we have a free afternoon, my nine-year-old and I visit our favorite bookshop. By now, we have a routine. Ella makes a beeline to the graphic novels.

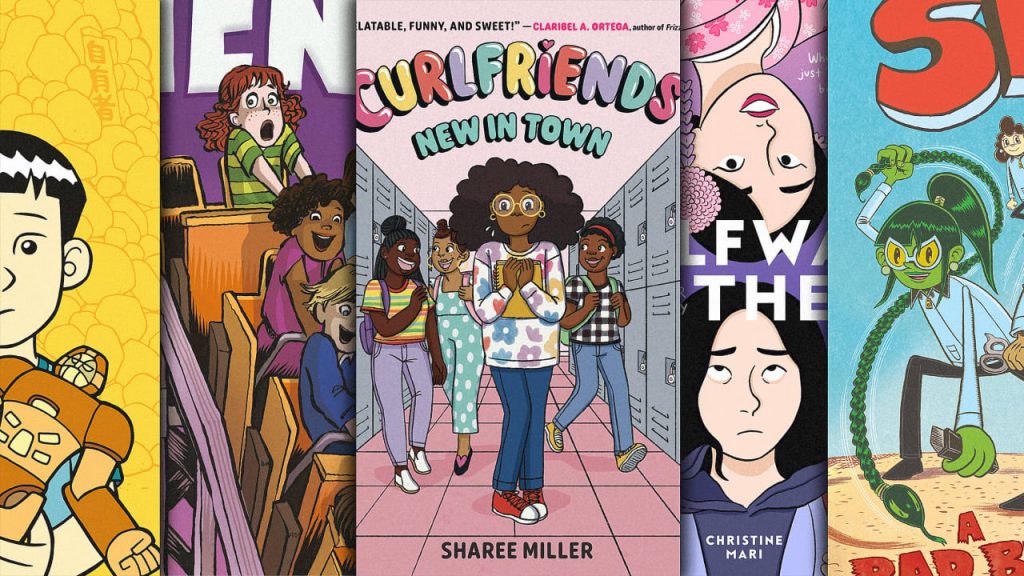

Her favorite books—such as Smile, Roller Girl, and The New Girl—are part of a new genre of graphic novels that has emerged over the past decade-and-a-half specifically targeted at eight-12-year-olds. The books’ illustrations are colorful and fun, but the stories tackle serious issues: Mending broken relationships; confronting social anxiety; dealing with siblings and parents.

Unlike prose, which takes her days to read, Ella will binge these graphic novels in less than an hour. But she’ll come back again and again to the ones she loves, as if they’re guidebooks for navigating life’s tricky situations. Still, at this pace, we need a constant stream of them. Fortunately for her, we’re in a golden age of graphic novels.

Publishers are now churning out thousands of new titles every year for readers of all ages, from the youngest readers to adults. Graphic novelists are pushing the boundaries of the art form, telling a wide range of stories in varied illustration styles. And more people than ever are reading these books. Since 2019, sales of graphic novels in the U.S. have doubled to 35 million books a year, a number behind only general fiction and romance.

Graphic novels—a term interchangeably used with comic books—are particularly popular among young children still building their literacy skills. Surveys show that in recent years, graphic novels have increased in popularity by 69% among elementary school children. Several publishers now have specific children’s imprints devoted to graphic novels, including Macmillan’s First Second and Hachette’s Little, Brown Ink.

My husband and I have observed Ella’s love of graphic novels with curiosity and, if we’re honest, a little skepticism. We’re not alone. More than half of school librarians report that parents and teachers oppose the genre and don’t think it’s a legitimate form of literature. This hesitation makes sense. Most millennial parents didn’t grow up with graphic novels and they now have questions about how these books will shape their child’s lifelong relationship to reading. Will kids ever make the leap to more traditional prose? And ultimately, does it matter?

How Comics got a bad name

Comics first emerged in the early 1900s, when newspapers published humorous serialized comic strips. (Think: Peanuts, Beetle Bailey.) In the 1940s, the comics industry exploded, as creators told stories across many genres including horror, crime, and perhaps most famously, superheroes. By the ’50s, Superman comics were selling at a rate of 1.5 million copies a month.

Then came a backlash. Comics of this era were often written for adults, depicting violence, drugs, and sex. In 1954, the psychologist Fredric Wertham wrote the book, Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth, which asserted that comics had a negative impact on children, pushing “deviant” sexual practices on them. (His examples now seem far-fetched and prudish, including the bondage subtext of Wonder Woman’s lasso, and homosexual undertones of Batman and Robin’s relationship.)

The U.S. government began to worry about how comics were influencing American youth. At a Senate hearing in 1954 about comics’s deleterious impact on society, mainstream publishers agreed to censor themselves, self-imposing a restrictive “Comics Code,” which ensured that all comics would be safe for children to read. Meanwhile, creators of comics with more adult themes went underground, selling their work on the black market. “Comics as an art form regressed,” says Eva Volin, supervising children’s librarian at the Alameda Free Library in California. “Many comics publishers went out of business.”

By the time I was growing up in the ’80s and ’90s, comics as a genre had largely petered out. The series that remained were formulaic and tame—like Dilbert or Garfield—rather than the rich, exciting stories from previous decades. There was still a community of superhero fans reading DC and Marvel comics, but they didn’t have the same kind of widespread appeal. “The attacks on comics had a chilling effect that persisted for decades,” Volin says. “Some people continue to see comics as something base and potentially harmful.”

But in the midst of this dearth, small communities of comics-lovers persisted, says Robin Brenner, head of reference and programming at the Woburn Public Library outside Boston. Some scratched the itch by turning to Manga, a comics style from Japan that spanned a wide range of genres and ages. By the early 2000s, Japanese publishers were translating and exporting these books around the world. There was also a new subculture bubbling online around webcomics, where creators published serialized stories on the internet that dropped once a week.

American publishers took note. “[Publishers] suddenly realized there could be an enormous market for comics that told different kinds of stories, for different audiences,” says Brenner.

The New Genre of Tween Graphic Novels

Tori Sharp, a 30-year-old graphic novelist, has always loved comics. “I found that so much voice could come through the artwork,” Sharp says. “There’s something that feels like you are a step closer to the creator than you can get with prose. It feels so intimate.”

Throughout her childhood, though, she struggled to find books in the genre. Even a decade ago, when she was in art school at SCAD, the library had only a handful of well-known titles, such as Maus and Persepolis. But as she was training to be an artist, the plate tectonics in the children’s graphic novel market was shifting.

One breakthrough moment happened in 2010 when Scholastic published Raina Telgemeier’s book Smile, a graphic novel about a sixth grader who injures her two front teeth and must wear embarrassing headgear. The relatable story, with its colorful illustrations, was an instant hit among early readers and middle schoolers. It sold tens of thousands of copies the year it was released, and a decade later it was selling hundreds of thousands of copies annually. Telgemeier went on to create many other bestsellers, including a graphic novel version of The Baby-Sitters Club.

Andrea Colvin, the editorial director of graphic publishing at Little, Brown Ink, says that Telgemeier ushered in a new genre of comics targeted at tweens. Soon, all children’s publishers were eager to acquire books by talented graphic novelists focused on the topics that middle-grade readers cared about. “It was such an exciting moment,” says Colvin. “There was this new medium for children to process stories.”

In her role at Little, Brown Ink, Colvin brought Sharp on to create graphic novels for middle-grade readers. For Sharp, this was an opportunity to create the kinds of books she had craved as a child. Her first graphic novel, published in 2021, is a memoir that explains how Sharp dealt with her parents’ divorce by living in her imagination. “I had thought about writing the story as fiction, with a little dragon whose parents got divorced,” she says. “But I felt that telling a story that kids would know was true could be really helpful if they were dealing with this particular issue.”

Many parents are turned off by the fact that kids go through graphic novels quickly, taking it as sign that these books aren’t as substantial as prose. But Sharp doesn’t see it that way. “One of the most beautiful things about graphic novels is how quick they are to read,” she says. “It allows kids to cycle through different stories, find one they connect with, and spend a lot of time with that particular story. Kids often read books with characters a few years older than they are, dealing with issues they’re curious about.”

Today, graphic novels are often the first books that elementary-school students will seek out for themselves and read on their own. And this is likely to shape a child’s lifelong relationship to reading. “This is a formative period in a child’s life,” says Namrata Tripathi, founder and publisher of Kokila, a children’s book imprint at Penguin Young Readers. “Their experiences with reading in these years will shape how they feel about literature as adults.”

Graphic Novels and Parents’ Angst

When publishers first started making graphic novels for young children in the 2010s, there was a lot of opposition. This resistance persists. According to the School Library Journal’s most recent survey, 55% of librarians said teachers opposed them because they were not “real books,” while 48% said parents felt this way.

Their concern comes at a time when there’s been a steep decline in children’s reading. Scholastic has found that as children go from elementary to high school, there’s a dramatic decline in their reading enjoyment (from 70% to 46%) as well as in reading frequency (46% to 15%). Scholastic says that one reason for this is that children are increasingly spending time on screens, particularly in their tween and teen years.

To many parents and educators, it’s unclear whether graphic novels are making the problem better or worse. With their bold illustrations and shorter word counts, the genre seems tailored to kids immersed in the deeply visual, high-velocity world of TV and video games. But these caregivers worry that kids will never make the transition to reading prose, that they’ll end up in college without having read an entire book.

But new data suggests that graphic novels actually do help cultivate lifelong readers of prose. A 2023 survey from the National Literacy Trust found that children who read graphic novels in their free time were twice as likely to enjoy reading more overall and rated themselves good readers as compared to those that did not read graphic novels. To Tripathi, this makes sense. “As parents, we can feel a certain pressure to make reading very metrics-oriented, wanting them to read books of a certain length or with a certain number of words,” she says. “We forget that the kid who is going to stay a reader is one who loves reading, who associates it with a kind of pleasure, joy, curiosity, and fulfillment.”

Publishers have had to fight to show the world that graphic novels are a legitimate form of literature. The graphic novel imprint First Second, for instance, has been instrumental in this effort. Macmillan launched it in 2006, when graphic novels had only a small, niche audience. But from the start, it focused on acquiring books for children that pushed the boundaries of art and storytelling; many of its books have received prestigious awards. One of the first books it ever published, American Born Chinese, was a finalist for the National Book award. “I can’t stress enough how important the destigmatization process was,” says Jon Yaged, CEO of Macmillan. “Nobody can deny the literary merit of graphic novels anymore.”

With parents so fixated on making sure our kids are hitting literacy milestones, many haven’t noticed that children are developing an entirely new form of literacy that we don’t have. Many adults find graphic novels foreign and intimidating because it takes time to learn how to read them. “Kids are now fluent in a kind of visual literacy that their parents don’t even recognize as a skillset,” says Tripathi. “They have a nuanced understanding of symbols. They’re able to understand what is happening in the blank spaces between the panels.”

As I see Ella’s well-worn piles of graphic novels around the house, I think about how my daughter has access to an entire universe of storytelling that I didn’t have. And as the graphic-novel industry keeps growing, publishers are now working to create books for adults who grew up loving the format. The First Second team is now launching an entirely new imprint called 23rd Street Books that is devoted to adults. Ella will benefit from this explosion of literature in graphic novel form.

“We used to be the lone kooks in the wilderness,” says Calista Brill, editorial director at First Second, who will serve the same role at 23rd Street. “But comics aren’t niche anymore. For people like me, who love comics, a new world is opening up. Phenomenal creators are creating books that touch on every topic you can imagine, and the possibilities are endless.”