When artist Paul Gardère died in 2011, his daughter, Cat Gardère, undertook her promise to steward his estate and legacy. Having worked as a studio manager and an exhibition coordinator, “I had a lot of familiarity working with artists, archives, and studios,” she told ARTnews. She began the long process of fulfilling her commitment to her father, but there was one catch: the elder Gardère had not set up a trust.

First, she cataloged his assets to prepare the estate for probate—or an inventory and appraisal of artworks to secure ownership in court. Being the sole benefactor of her late parents’ assets meant having some financial resources to begin this work, which involved hiring archivists and working 40 hours a week over 3 years to document inventory and create a digital archive. By 2022, with this digitization largely complete but dwindling funds, she realized there was far more to do in advocating for her father—namely, the work of getting his art into exhibitions and collections.

On Instagram, Gardère saw that her high school classmate, Max Warsh, was posting about the work of his late aunt, the writer and textile artist Rosemary Mayer. Mayer had a posthumous retrospective at the Swiss Institute in New York in 2021, which traveled to three institutions in Europe. “I thought it was serendipitous that somebody in my network was also doing art estate work,” Gardère said. It ended up being a blessing.

Warsh connected her to the Artist’s Foundation & Estate Leaders’ List (AFELL), a Google group started by Chelsea Spengemann, with Tracy Bartley, in 2019 for others in this situation to share resources. AFELL’s more than 300 members range from individuals to operations like the Joan Mitchell Foundation and the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation. While much of its focus is devoted to helping steward the legacies of dead artists, some living artists, like Simone Leigh, have also used AFELL’s resources with the hope of learning best practices for legacy planning.

AFELL is just one outfit that has emerged in the past decade to help artists and their descendants ensure a future for their art. And as under-recognized artists get more and more attention within galleries and museums, these entities are increasingly important, working behind the scenes to help mount projects that would otherwise have been impossible.

Take the case of Soft Network, a New York–based operation that is “part shared workspace and active storage space for multiple artists estates, and part space for exhibitions and programs,” as Spengemann put it in a phone interview. Spengemann runs Soft Network with Warsh’s sister, the art historian Marie Warsh, and together they have helped steer the estates of Mayer and Stan VanDerBeek. They call their labor “legacy work.” This past September, they formerly launched AFELL as a part of their organization.

One such project was a Paul Gardère show held at Soft Network’s exhibition space, located down the hall from the operation’s offices in a SoHo building. In 2022, Cat Gardère was the inaugural participant in a burgeoning residency program run by Soft Network. “They said they would act as mentors and a support network,” Gardère recalled. The organization also presented a solo booth of Gardère’s work at the Independent art fair in September of that year.

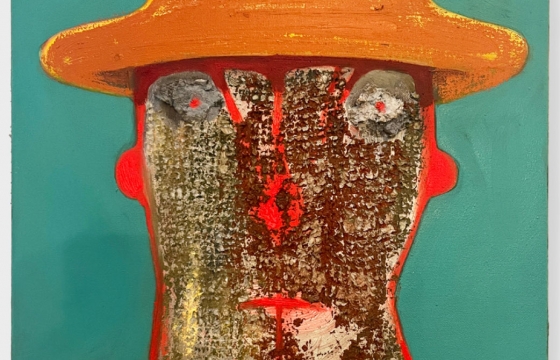

Cat Gardère credits this exposure with helping secure exhibiting opportunities, including a museum presentation of that same two-person show with Williams at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University. She also said her father was included in “Surrealism and Us,” a 2024 exhibition about of Surrealism in the Caribbean and the African diaspora that appeared the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, after Soft Network spotlighted his work. The curator of that exhibition, María Elena Ortiz, knew about his work but had never seen a piece in person until the Independent presentation. Without Spengemann and Warsh starting the conversation about his work, “I don’t that connection would not have been made,” Cat said. A solo survey of Gardère’s is currently on view in New York at Cooper Union.

In spring 2023, the second exhibition at Soft Network featured living artists’ works alongside a piece of public art by the late sculptor and performance artist Scott Burton. The Burton piece, Atrium Furnishment (1986), was originally installed in the atrium of the Equitable Life Assurance Company in New York. A seating arrangement combining marble, brass, onyx, and plants, Atrium Furnishment had never been restaged prior to this show. The curator of the Equitable Art Collection, Jeremy Johnston, gave access to the piece, which was put in storage after the company moved out of the Seventh Avenue building in 2016. Johnston independently runs a collaborative curatorial organization called Darling Green, and together with Soft Network they arrived at the concept and design for the presentation.

At first glance, Burton’s estate has steady institutional footing: in accordance with the artist’s will, the Museum of Modern Art agreed to take it after his death from AIDS-related causes in 1989. This meant MoMA was next in line to receive all of Burton’s art, archives and his copyright after his partner Johnathan Erlitz died in 1998. But MoMA “didn’t have a point person, or any structure around this history,” Spengemann said. A recent article by Julia Halprin for the New York Times delves into how the museum—despite its vast resources and position of cultural prominence—has been challenged to adequately manage this bequest.

With their 2023 show, Soft Network and Darling Green are among a few players bringing Burton’s work back into the spotlight. In 2022, the art historian David Getsy released a book about Burton’s art, and the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis is staging the first survey of Burton’s work in roughly four decades.

Spegemann and Warsh are seeking 501(c)3 status, and they currently run on private donations, grants, and consultancy fees based on a sliding scale. That means they operate on a nonprofit model, making them different from the similarly scaled Artist Estate Studio LLC, who does consulting for the estates of painters Jack Tworkov and Janice Biala, which cofounder Jason Andrew said is backed by client fees.

But these endeavors are on the smaller, scrappier side in this new frontier, with more well-known estates working with bigger firms like Schwartzman&. Allan Schwartzman conceived Schwartzman& in 2020 as an advisory whose services extend beyond individual collectors to artists and institutions. Over Zoom, Schwartzman told ARTnews that, upon starting this venture, he was “aware that the fields have become much more focused on the moment and the transactional. I decided as an adviser, I would do the opposite. And I would focus on various aspects of the ecosystem that that I felt were suffering.” In short, this is the work that goes into producing value for art—and typically the kind of thing left to galleries. But where agencies like Schwartzman’s differ is that they do not conduct sales, hence why galleries are still necessary to represent estates, even if they already work with his firm or a similar outfit.

Estate and legacy planning is one of Schwartzman&’s largest areas of growth. The advisory consults seven artist estates, including those of Jimmie Durham and Robert Rauschenberg. Schwartzman said he also works with “several artists of mature ages planning for legacy,” but he declined to name which ones.

A curator at the New Museum in 1977 before finding success as an advisor (his previous firm with Amy Cappellazzo was acquired by Sotheby’s for $50 million in 2016), Schwartzman has been thinking about legacy work for decades. “The first wave of baby boomers marked a dramatic increase in the number of artists,” he shared. “Now those individuals are past what usually would be considered retirement age, and very few, if any, have planned thoughtfully for their legacies.”

Solana Chehtman, the director of artist programs at the Joan Mitchell Foundation, corroborated this uptick in aging artists needing assistance with legacy planning. In an email, she described how the foundation’s CALL (Creating a Living Legacy) initiative was conceived in 2007 as a grant program, for artists to self-direct the use of funds.

“It quickly became clear that artists didn’t know how to go about this work,” she wrote, “so we started training ‘legacy specialists’ that we partnered with the artists to support them in organizing their studios, documenting and inventorying their work, and crafting the narrative behind their trajectory.” She’s seen the growing demand for this knowledge. In response, the foundation has compiled and published free “CALL workbooks,” which outline the knowledge accrued by their specialists. The workbooks are often referenced by the AFELL community as a starting point for members navigating these new waters.

Yet even among artists who have adequate estate planning with legal counsel, Schwartzman has noticed that the many other facets of estate stewardship are rarely breached during an artist’s lifetime. He acknowledged, “Not a lot of people want to deal with questions of: What happens when I’m not here?” Nor can they, and according to him, that means a lot of the advisory’s work centers on how to keep an artist’s practice in the mix of present-day markets and critical discourse.

With Gladstone Gallery in 2022, the Rauschenberg Foundation embarked on showing a body of work that had not been exhibited since the 1970s. The works on view—assemblages made from materials like sand, wood, and bicycle wheels—are a departure from his well-known “Combines” of the 1950s and his silkscreened paintings of the 1960s. “I think there were certain assumptions about Robert Rauschenberg that were reinforced by the market that were inaccurate,” Schwartzman said. “There was the sense that he really didn’t do that much that was innovative after the silkscreen paintings … so we showed a body of work that has no imagery in it.”

The Rauschenberg Foundation is an anomaly among foundations and estates in that it has worked with blue-chip galleries for many years, including Gagosian, Pace, Thaddaeus Ropac, and others before formally joining Gladstone’s roster in 2022. Lesser-known estates have generally had to continue without gallery representation, but that changed over the past few years.

Mega-galleries have increasingly been adding estates to their rosters. Hauser & Wirth today represents 38 estates, among them those of Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Cathy Josefowitz, and Ed Clark. Some of these are artists had galleries worked with during their lifetime, but few had a representative with as much power and money as Hauser & Wirth. Its competitors have also gotten in on the business of representing estates: Pace Gallery recently took on the estate of Jiro Takamatsu, and David Zwirner scooped up the Robert Ryman estate from Pace in 2021, two years after the artist died.

Surveying these galleries’ rosters, it’s clear that dealers are keen to find so-called rediscoveries. When David Zwirner began representing Alice Neel in 2008, she did not have an extensive market. But after her portraits figured in a Metropolitan Museum of Art retrospective in 2021, they became a market success, with her auction record hitting $3 million that year.

Still, as dealer Sam Gordon, a co-owner of the New York gallery Gordon Robichaux shared, “There are easier ways to make money.” The works of many under-recognized artists do not command top dollar. Dealers like Gordon who work extensively with estates focus more on getting these artists into institutional collections and building audiences for their work.

Gordon Robichaux represents a handful of late artists, and Gordon said that this is more the result of access and personal interests than a business decision. The gallery brought on the Rosemarie Mayer estate through friends and years of familiarity with Max Warsh. “We did what any good gallery does and connected the dots,” he said. After the success of Mayer’s museum shows, the gallery and estate linked-up in a sales capacity, ultimately placing pieces in public collections, including MoMA.

Another estate on the roster, the Jenni Crain Foundation, preserves the legacy of the curator and artist who died in 2021 at 30 from complications related to Covid-19. The gallery began exhibiting Crain’s work in 2018 and started representing her soon after. Her sudden passing at a young age meant many of her sculptures, with interlocking components, exist as instructions that gallery and foundation are constructing and exhibiting. The challenge comes with how to speak for an artist whose work exists, and should be shown alongside, peers who are very much alive and vocal about how their work is presented.

Sales, acquisitions, exhibitions, and scholarship are all steps forward for the estates, foundations, dealers and advisors embarking on legacy work. For an organization like Soft Network, this endeavor also involves focusing on something more abstract: generating inspiration for living artists via the estates under their purview.

Burton’s Atrium Furnishment is receiving even more attention as the sculptural bones of an installation by Álvaro Urbano currently on view at SculptureCenter. Urbano first met Soft Network’s Marie Warsh at a party in his home city of Berlin, which led to her sharing the history and whereabouts of the disassembled installation.

“When I was living in New York as a young artist I was interested in the possible meeting points between architecture and design and art,” Urbano said in an email. He was familiar with public works by Burton around the city and was keen to draw parallels between these constructed environments and the Ramble at Central Park, a longtime cruising area and refuge for gay communities. “I was attracted to how the piece initially presented itself as very strict and formal” Urbano said of Atrium Furnishment’s highly orchestrated masonry. “However, the work provided a space of refuge within its original corporate setting for workers who wanted to take a rest or have a chat.”

In SculptureCenter’s grand industrial space, Urbano has installed a faux drop-ceiling with a gradient lighting program. This hangs over a de-constructed rearrangement of the original installation’s marble and onyx decor, which he covers in delicate metal sculptures this kind of blooms found in Central Park. These flora, in Urbano’s words, “act as symbols of rebirth and resistance, with the hope that Atrium Furniture will eventually find a permanent home and a proper setting.”