Four hundred years ago, at the intersection of what is now 11th Avenue and West 54th Street in Manhattan, an oak-tulip tree forest wrapped along the coastline of the island. During this period, when the Lenape tribe still called the island of “Manahatta” home, the landscape was as biodiverse as Yellowstone. Today, the neighborhood, currently known as Hell’s Kitchen, is dotted with luxury car dealerships and bodegas.

Nine stories above a Land Rover shop, a version of this ancient ecology is coming back to life in a brightly lit cube. Tree saplings and other flora fill a large planter. A grid of tubes hidden inside the walls and ceiling pipe in oxygen, carbon dioxide, and other gasses to replicate the exact conditions of the same day in 1864—the first year New York City’s weather was recorded.

“We have established one of the most biodiverse ecosystems in New York City right now,” says Neri Oxman, as she stands in the middle of a soaring atrium, gesturing in the direction of the lab where the planter sits. The former MIT professor, known for her cerebral design projects, is showing me and a group of journalists around her new design studio, called OXMAN.

She opened OXMAN last fall following five years of building it in stealth. The space—double height, gleaming white, and meticulously organized—was designed by the superstar architecture firm Foster + Partners. Across the hall, Oxman’s husband, the billionaire hedge fund manager William Ackman, runs his fund, Pershing Square Capital Management.

Oxman’s studio is equal parts science lab and art gallery. It is, in many ways, the physical embodiment of the career Oxman has charted since she became a professor at the MIT Media Lab in 2010. Oxman is trained as an architect, but only nominally puts those skills to use today. Instead, her work, which she refers to as “Material Ecology,” straddles an unusual cross-section of disciplines that include biology, technology, architecture, and industrial design.

Within her field, Oxman is often referred to as a “rock star”. She has won a National Design Award, given a popular TED talk, designed a mask for Bjork, and created work that’s on view in the permanent collection of some of the world’s most prestigious museums. She appeared on Fast Company’s cover in 2009 for her work at the MIT Media Lab, an unorthodox research lab focused on innovation and creative technologies. Outside of the lab, she is perhaps better known for briefly becoming tabloid fodder after Brad Pitt visited her lab in 2018.

Oxman’s work tends toward the fantastical. She has made 3D printed “death masks” designed to visualize the wearer’s last breath, and constructed a gossamer pavilion with the help of 17,500 living silk worms. In 2020, the Museum of Modern Art showed Oxman’s work in a solo exhibition. Paola Antonelli, the show’s curator and Oxman’s longtime friend, has said that Oxman’s work, while artistic in nature, is valuable because it’s rooted in real science. “Neri is always believable because, while her design is arrestingly elegant and could be enough for anyone interested in objects for their own sake, her science is strong and her technology effective,” Antonelli said during an interview leading up to the show.

Oxman, who is 48, has the waifish stature of a dancer with a mop of dark curls that often overflow from a messy bun. She started building OXMAN in 2019, amid big changes in her life. A new baby, a new husband, and a sky’s-the-limit budget to build a studio to her exacting vision. Ackman declined to comment for this article, but his and Oxman’s investment in the studio has been around $100 million so far. Oxman and Ackman are currently the sole investors of the studio, “other than a small but symbolic investment from Bill’s father, who died in 2022,” Oxman says. With that money, Oxman has ambitions to reshape the built world.

Designing for nature centricity

On a morning in October, Oxman was sitting in her glass box of an office, surrounded by samples of 3D printed mesh and colorful resin beads that her team had infused with the scent of the 200-year-old blueberry bush growing in the lab upstairs. Oxman describes the studio as an “intellectual space.” She currently has a few dozen employees: “11 PhDs and 12 master’s,” she says, mentally accounting for the brainpower she has amassed under one roof. Plus a handful of people with less notable academic bona fides. Six of her current employees were researchers at her Mediated Matter lab at MIT and followed her to OXMAN to translate their esoteric research into commercial products.

Oxman views the studio as a descendant of Bell Labs, the famed New Jersey research lab behind the creation of the transistor, solar panels, and a host of other formative technologies. If Bell Labs was responsible for setting the stage for the current technological landscape based on silicon, then Oxman hopes her studio will lay the foundation for the next technological age in which humans tap nature as a new form of computer.

“The ultimate elevator pitch is—and it’s a humbling one to state, because it is ambitious, and it is radical, and you know, massive in scale—to design for nature-centricity,” Oxman says. Oxman explains that “nature centricity” requires treating nature and humans as collaborators instead of adversaries. For much of the industrialized era, humans have extracted value from the earth, giving little, if nothing, in return. She believes the relationship between humans and the built world could be more mutually beneficial with the help of technologies like synthetic biology, AI, and additive manufacturing.

Currently, the studio has one public client, the Australia-based developer Goodman Group, who commissioned OXMAN to come up with a master plan for its data center developments that would, in the Goodman Group’s words, “maximize the ecological presence and utility of the built environment.”

Oxman and her team are using AI to explore optimized building structures and sites for the company’s data centers, a genre of building that has historically been a detriment to local ecologies and a major source of carbon emissions. Using custom-designed software to tweak parameters in real time—for instance, the permeability of surface materials, the placement of native plants, or the location of a building—OXMAN’s team can better tune the site to the needs of nature. “We want to be invested in something like data centers because it provides us with a really challenging context to test these ideas,” says Nicolas Lee, who studied under Oxman at MIT and is now Oxman’s head of ecology.

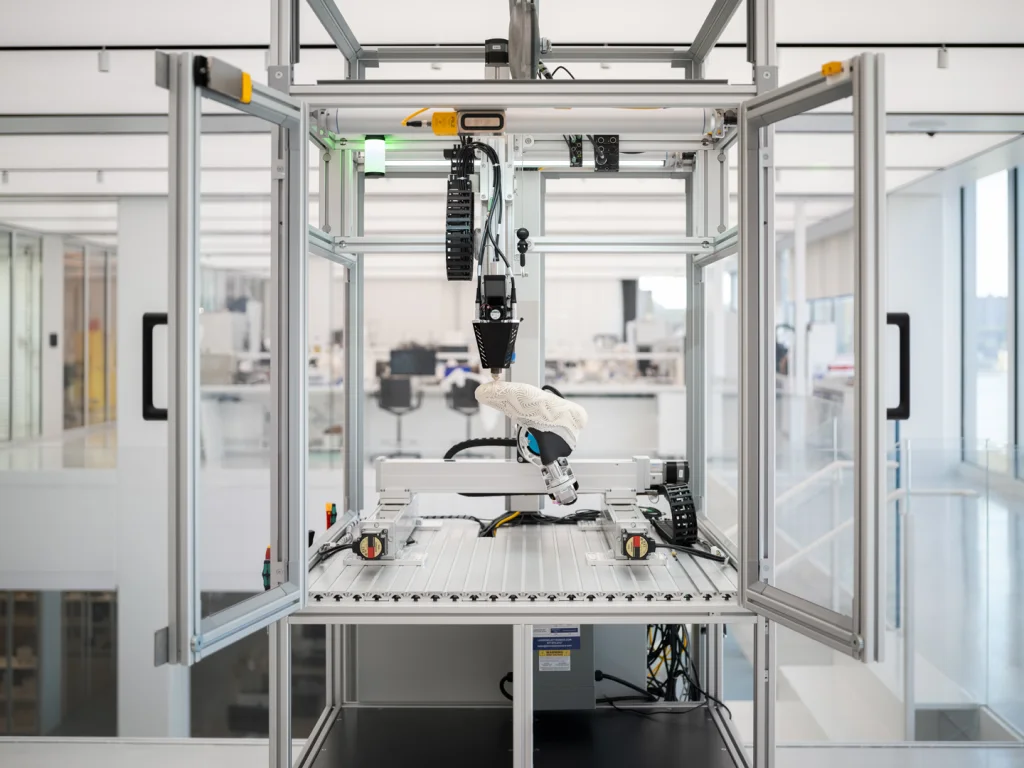

Alongside its architectural work, the studio’s first crack at a nature-centric product is a 3D printed shoe produced by a series of custom-built robots called the Oᵒ platform. The day I visit the lab, Oxman is wearing a pair of off-white ballet flats whose upper is made from waxy-looking squiggles. “We’ve just started wearing them as a team to test out the various mechanics,” she says, lifting her foot above her desk.

Oxman explains that the shoe is 3D knitted and printed with PHA, a thermoplastic polymer that her team is tweaking to achieve specific characteristics. The shoe she is wearing is infused with scent volatiles from the ancient ecology her team is reconstructing in the studio’s wet lab. Other shoes made by the Oᵒ robots might include features like genetically encoded messages or biological pigmentation.

Oxman’s ultimate aspiration is to create a shoe that can achieve what she calls “programmable reincarnation.” “Our goal is to program timed decomposition into the product,” she explains. The Oᵒ shoes are formulated to break down in the presence of soil and moisture. Eventually, they will be programmed to nurture the land as they disappear with the help of bacteria species that increase plant probiotic properties. “These shoes are entirely biocompatible,” she says. “Theoretically, you could eat them.”

I tell Oxman that I would be unlikely to eat a shoe, even if it were hypothetically possible. “Yes, but you would eat the apple from the tree that grew in a soil that was nourished by the shoe,” she responds, noting that by wearing this ballet flat, one could theoretically rewild an ecosystem. “I know this sounds wild,” she admits. “But this is the world that we’re heading into.”

Oxman’s team believes that people have been misled by the way sustainability has been sold to them, which has largely focused on circularity and recycling. “We are all programmed to think that waste is inherently bad, because for most of human history it has been. But if you look at nature, waste is a very different thing,” says Lee. “What we want to understand is, how can we take something like a biodegradable material and push the narrative forward to say that it’s not just about getting it away from us, it’s about giving it to the organisms that need it to do something else.”

For Oxman, the shoes are a tangible, if not fully realized, example of nature-centricity. She hopes they will help consumers and eventual commercial partners to better understand the abstract potential of her vision. “Is there a world in which driving a car is better for the natural world than not driving a car?” Oxman asks rhetorically. “Is there a world in which wearing a shoe is better for the natural environment than not wearing a shoe?”

Currently, the answer to both questions is no. Though closing the gap between a definitive no and maybe is a sweet spot for Oxman’s research. Oxman’s work has been criticized by some as being detached from current realities. “The end result of Oxman’s process is always an uncanny artifact of technofetishism,” architecture critic Kate Wagner recently wrote of Oxman’s architectural consulting work on Francis Ford Coppola’s recent film Megalopolis. Yet, Oxman doesn’t shy away from the enigmatic aspects of her work. “The nature of the practice is very, very long term,” she says.

Many of the problems Oxman’s team is working through are at least 10-year problems, says Che-Wei Wang, a designer who worked as OXMAN’s head of industrial design until recently. “It is an enormous challenge; I would say near impossible,” he says. “If anybody else approached me to do this kind of work, I’d be like, ‘you’re out of your mind, it’s not possible.’ But I think coming from Neri, both her as a person and also the resources that she has access to—if anyone can do it, this is the place where it’s going to happen.”

The path to Oxman

Oxman was born in Haifa, Israel, where she grew up surrounded by people who made things. Her grandfather ran an engineering studio, her grandmother was a public intellectual, and both of her parents were architecture professors. From a young age, Oxman displayed a whimsical curiosity about the world. As a child, she would visit her grandmother’s garden every day after school. She recalls spending hours staring up at the clouds and thinking about the passing of time. “If you asked me to use one word to describe my childhood, I would say innocence,” she says. “The kind of innocence I don’t see in our children, and how we raise our children in our cities today.”

After high school, Oxman joined the Israeli Defence Forces as a member of the Israeli Air Force before studying medicine at Hadassah Medical School. She left the school to study architecture, eventually landing at MIT for her PhD before joining the faculty in 2010. Oxman believes that humans tend to reboot every 10 years. “You have the opportunity to reinvent yourself,” she tells me. For Oxman, deciding to leave MIT was one of those moments.

In 2019, leading up to her departure, the MIT Media Lab had been in tumult after an investigation found that Jeffrey Epstein, the late hedge fund manager convicted of sex trafficking minors, had donated $850,000 to the Media Lab. Oxman, among other Media Lab researchers, was the recipient of a large donation (her Mediated Matter lab received $125,000 in 2015). Oxman issued a statement and apology for accepting the donation. “I regret having received funds from Epstein, and deeply apologize to my students for their inadvertent involvement in this mess,” she wrote at the time.

Oxman, who was on maternity leave when the news broke, had already begun thinking about opening a studio before MIT’s Epstein entanglement became public. She says leaving MIT was a conscious choice to realize the kind of research her team had been conducting within the confines of academia, publishing, and museum shows. “I was intrigued, as a designer and as a maker, by the ability to make real change in the world,” she says.

Oxman credits Ackman, who she met in 2017, with pushing her to think beyond her work as an academic. She recalls receiving a text from him in late 2017, encouraging her to leave. “He said, are you able to put a cliff behind you and jump?” Oxman says. “I was very comfortable at MIT.”

After her daughter was born in 2019, Oxman began conversations with MIT about scaling back from tenure to a professor of practice position. “It would have allowed me to visit there less often than daily,” she says. “I wasn’t sure about that because I am very much kind of an all-in woman.” By 2020, she told MIT she was leaving to start a new company. “I found myself in a comfortable home, in a privileged position, and felt very, very much inclined to make that leap,” she says.

Oxman’s decision dovetailed with another moment that she says was formative as she started to think about her nascent studio. She received a call from her friend, Ron Milo, a professor in the Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science. Milo told Oxman about a paper he was about to publish in Nature that detailed how, for the first time, human-created mass had exceeded living biomass. The world had crossed a threshold to become irreversibly altered by humans.

“I had goosebumps,” Oxman recalls. “All I could think of was my daughter in the other room, across the hall.”

Building Oxman

While she was still at MIT, Oxman had started talks with Foster + Partners about building out a space for her studio. The architects were already working on her and Ackman’s new home—a glass-walled penthouse that overlooks Central Park, reportedly bought for $22.5 million.

As Oxman’s ambitions for the studio grew, so did her need for space. “When [the project] first started, it was a third of the size,” says Russell Hales, a partner at Foster + Partners, who led the design. “We ran out of space twice.” Oxman decided to expand the studio from one floor, shared with Ackman’s hedge fund, to two. The thinking being that the studio would need to be able to flex with new technology over the years. “This is a project that she wants to live and work in for 50-plus years,” says Hales. “Adaptability was key.”

Oxman’s initial sketches for the space were unorthodox by the standards of most design studios and science labs. She envisioned a lab where biologists, chemists, botanists, and other scientific disciplines could run experiments alongside each other, while engineers and architects were just a few steps away. “You can move from a robot to a computer to a pipette in a matter of 30 seconds,” Oxman says of the current layout.

One of Oxman’s early ideas for the wet lab featured a car chassis in the middle of the room—a thought experiment to get Foster + Partners to think differently about what a lab space could look like. “All the furniture was modular and could be moved around very easily, so you could open the space up completely,” Oxman recalls of the concept. “[You could] take all the furniture out and place a car chassis, or a portion of a rocket, or a very, very large thing that could be designed using bio-based tools.”

Today, the lab is outfitted with heavy lifting points that allow up to 500 pounds to hang from the ceiling, while the downstairs atrium features a soaring ceiling that accommodates objects up to 25 feet tall. Throughout the space, custom-designed power strips called “superchargers” provide power and data access, so researchers can move freely throughout the studio.

Hales says Oxman was exacting in her vision for the space. “You’ll notice all the lights line up with the lab furniture, which line up with the superchargers in the floor, which line up with the way the desks work over two stories,” he says. “Having organization in all that sort of stuff that’s normally clutter creates a calmness. It’s slightly obsessive, but it produces this kind of very calm-on-the-eyes space, which Neri really responded to.”

One of Oxman’s favorite details in the studio is a row of four environmental capsules that function as experimental growth chambers where the team can fine-tune inputs like gases, humidity, airflow, lighting, and data. The rooms’ transparent glass doors were designed to function like the airtight doors on a yacht, enabling the rooms to be used as large-scale test tubes.

On the day I visited, one room was growing ancient plants and another was running testing on the PHA shoe’s degradation. But in theory, the capsules could be used to grow tissue culture or perform other biological experiments. Oxman likens the rooms to a three-dimensional computer that can be programmed for whatever experiment needs to happen. Like most other aspects of Oxman’s studio, the capsules were custom-built to her vision. “There are no rooms like this,” she says.

One of the studio’s goals is to decode the molecular fingerprint of plants so the team can use the information to design products that harness their unique functions. The team is currently studying the biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs) that plants in the ancient ecology emit as a way to understand how the plants communicate with each other. “BVOCs can have both messages and influences, and that’s why we’re interested in them,” explains Sarabeth Buckley, a plant scientist with OXMAN. “We see them as a type of language for nature that we hope to decipher with time.”

Oxman says understanding this language is a vital step in creating products that work with nature. Imagine a volatile that attracts pollinators, she says. “If you bring that volatile into the product space, what could you build? Could you design a wearable or a shoe that attracts pollinators?”

As a first step, the team has been working with the New York Botanical Garden to reconstruct a miniature ancient ecology in one of OXMAN’s growth chambers. Eric Sanderson, a landscape ecologist and Vice President for Urban Conservation Strategy at the NYBG, says Oxman’s work is unlike anything he’s seen from researchers who collaborate with the NYBG. “She thinks in such different dimensions than most scientists do,” Sanderson says. “She puts things together that are so traditionally separate from each other in new and interesting sorts of ways.”

For Sanderson, whose path has hewn more closely to traditional science, Oxman’s approach is both “incredibly exciting and also a little bit frightening at the same time.”

“She talks about manipulating environments to get species to do things that they wouldn’t otherwise do,” he continues. “I come from a conservation background where it’s more about letting species do the things they want to do—removing human influence, not adding human influence, right? So that idea feels a little uncomfortable to me. But, on the other hand, as I said before, Neri is very compelling and kind of persuasive in her vision.”

Yin and Yang

In the year leading up to the launch of her studio, Oxman dealt with a situation that knocked her from her ideological perch and into the realities of building a business as a public figure. In early 2024, Business Insider accused Oxman of plagiarism in her 2010 PhD dissertation. Oxman quickly apologized and clarified the error on X with a detailed explanation of the missing quotation marks and citation.

In less divisive times, the contents of a dissertation titled “Material-based Design Computation” would have remained in the annals of niche academia, but the moment was mired in cultural tension. Business Insider’s story came on the heels of Ackman’s public push to get then-Harvard President Claudine Gay to resign after multiple instances of plagiarism were found in Gay’s academic work (Ackman was a vocal critic of Gay’s response to antisemitism on Harvard’s campus in the aftermath of the October 7 attacks in Israel).

The situation exploded into virality after Ackman came to Oxman’s defense online, and hired Clare Locke, a law firm well known for bringing defamation cases against news outlets, to send Axel Springer, Business Insider’s parent company, a 77-page demand letter asking for a retraction. Axel Springer conducted an investigation into the reporting of the story and found no wrongdoing.

Oxman says she has since moved past the drama, and feels stronger for having gone through it. “[At] the end of the day, what we do happens in the physical world, and happens as part of a system of interaction and transactions,” she says. “And it doesn’t all happen at that very higher ground which I would have otherwise occupied—the spiritual dimension of me.”

During politically charged moments like this, Ackman and Oxman appear an unlikely match given Oxman’s altruistic flavor of optimism and Ackman’s penchant for online squabbling. Oxman thinks of Ackman and herself as yin and yang. The night before I visited Oxman at her studio last fall, she and Ackman were at home, and “Bill was sending a tweet about the looming threat of nuclear weapons in Iran while I was talking to my rabbi,” Oxman recalls. Oxman says she pushed the door shut between them. “And as I was closing it, I thought, Wow, I’m drawing the line between the yin and the yang.”

But these lines aren’t so easily drawn for everyone. Before the 2024 election, Ackman, a longtime Democratic donor and early proponent for replacing Biden on the Democratic ticket, became a vocal supporter of Donald Trump. The endorsement became a source of tension among the studio’s employees, who view the stance as at odds with OXMAN’s long-term vision for improving the planet’s health.

Oxman waves away any possibility that Ackman’s politics were disruptive when asked about it. “The tension that was felt here was no bigger than the tension that was felt in the real world outside of this door,” Oxman says. “But I do my best to mother. I do my best to preside over the team. As we say about the work we create—we create the future while living in the current world with its current limitations.”

Productive frictions

Those who know Oxman say she has an undeterrable ambition. “She is one of the great thinkers and doers of her time in design,” says the technologist John Maeda, who has known Oxman since she was a PhD student at MIT. Whether or not Oxman’s vision for the future is commercially viable is a question that’s still unanswered.

“The real grounding reality, and the nature of the business, is what keeps us going,” says Oxman. “Otherwise we would be an art practice.”

During a recent video call, Oxman held up a paper to show me a diagram depicting the studio’s path to creating a shoe that can fully reincarnate. Earlier that day, she had shown the same diagram to members of the shoe team. “I said, ‘Look, we’re in point A where the shoe is not yet at the level where it can completely reincarnate into another product . . . and it cannot completely augment a plant. But we can create a shoe with zero microplastic, and that’s a big deal.’”

Oxman accepts the incremental nature of scientific progress, though she views it as a stepping stone to actualizing her more ambitious ideas. She says that in order to achieve the impossible, you have to suspend disbelief. She views the studio as a place where she and her team can disengage from certain aspects of reality, though she knows it’s always right outside her door. “I do my best to set [the studio] up as its own microcosmos that embodies that innocence, which I had as a child,” she says. “And I want to give to other team members as a kind of a modus operandi in this creative space. But again . . . we do not live in a vacuum.”

Oxman tells me that she considers the studio to be in its “Cinderella moment,” when potential clients and collaborators can finally see what the studio has been building for the past five years. Sitting in her office, surrounded by the creations from her past life and the beginnings of her new life, Oxman wonders aloud about how her studio will inch towards self-sufficiency. She acknowledges that there is an inherent tension between scientific idealism and capitalism, between research and commercial production, and between a higher vision and the harsher realities of the world.

“What is the fate of a shoe and a scent and an architectural approach? Where does each of these projects go, practically, commercially,” she says. “We are in the midst of dealing with those productive frictions.”